Foreword

This report explores the experiences of disabled people using the benefits system. It highlights the challenges disabled people face. And sets out what disabled people told us needs to change.

We have known for a long time that the benefits system is complex. That accessing it can lead to stress and anxiety. And that the system is too-often based on catching people out.

This report makes it clear how common these experiences are today.

Disabled people we spoke to told us that they fear having to access support. That they worry about discrimination. And for those who can work, there is little support if a job does not work out.

Disabled people also told us that it is a fight to access financial support. Many said that the system is too complex.

It is clear from this research that major reform and change is needed.

Participants spoke often of ‘trust’ being the foundation for a better system, and of the need for empathy and kindness. Too often, people said they were not believed, have been made to feel second-class, and were left in impossible situations.

We hope that this research acts as a wake-up call to Government, to policy makers and to those involved in the benefits system. We know that tinkering at the edges will not change much. But we know what will. We must rebuild our welfare system so that everyone who needs to use it is treated with kindness and respect. And, crucially, that they are trusted as experts of their own lives.

We are grateful to the participants of this research who shared their experiences of work and navigating the benefits system with us.

Finally, we are grateful to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation for funding us to undertake this work.

Executive summary

What is in this report?

Scope and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation have partnered for this research. This report explores the experiences of disabled people using the benefits system. It highlights the challenges disabled people face. And sets out what disabled people told us needs to change.

Background

We know that life costs more if you’re disabled. Many disabled people who receive Universal Credit live in serious poverty. Most struggle to afford basic needs. And around half are experiencing food insecurity. This means their households had to reduce the amount, quality or variety of food.

In recent years, disability benefits in the United Kingdom (UK) have been a target for budget cuts across different governments. While the government and the media often talk about the low number of disabled people in work, the focus is mostly on cuts to benefits instead of fixing the barriers to employment.

Even though many disabled people want to work, there is still a gap of around 30% between disabled workers and non-disabled workers. And disabled workers are also more likely to have unstable jobs.

What did the report find?

We asked disabled people on our Lived Experience Research Panel about their experiences of using the UK benefits system. And what they thought could make the system better. This is what they told us:

The benefits system lacks understanding.

There is poor understanding of disability throughout the system. Disabled people feel that it is not there to support them.

The system is failing disabled people.

The system is not working for disabled people who cannot work. It also does not work for those who are already working or wanting to work.

The process is confusing and stressful.

People struggle to understand how the system works and what support they can access. Assessments cause a lot of anxiety and do not address the real barriers disabled people face. Often, disabled people feel they are not believed. They are treated as second class citizens and left in difficult situations.

Disabled people are harmed by pressure and shaming around benefits.

Government and media rhetoric impact negative public attitudes. People are made to feel unvalued by society and many feel forced to justify needing to claim.

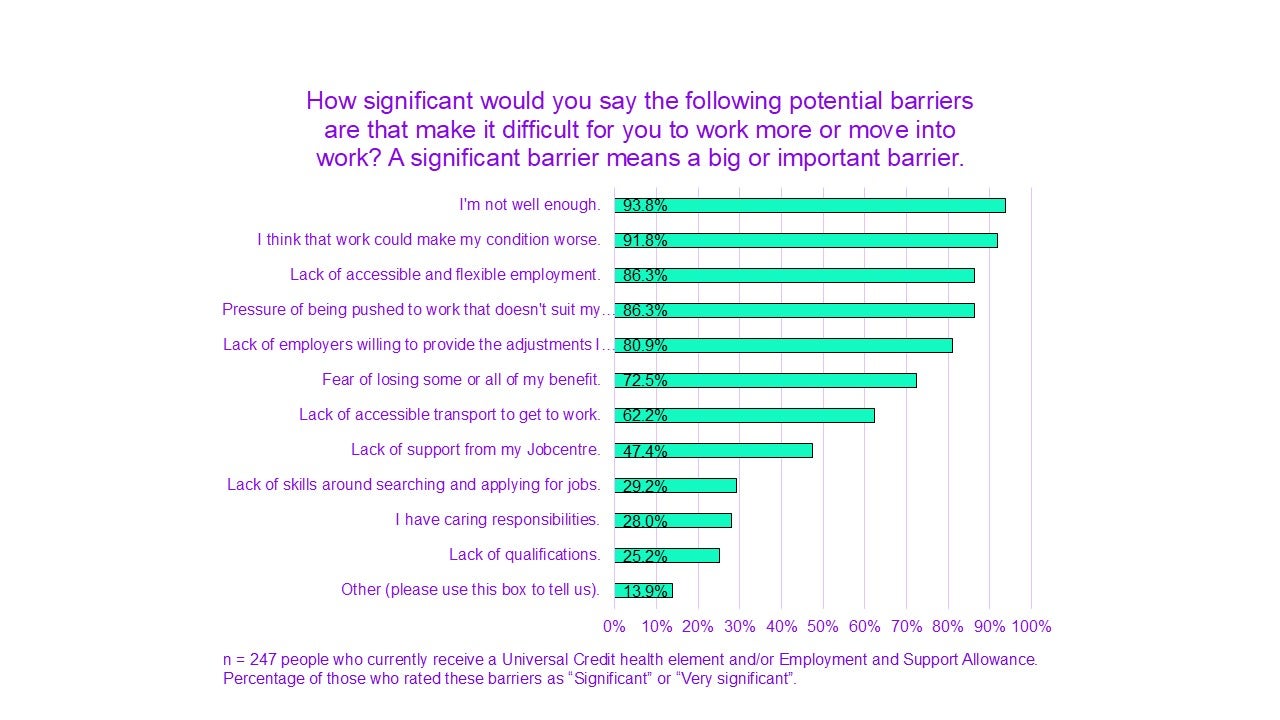

Health and the job market are the real barriers.

The biggest barriers for disabled people entering the job market are not a lack of skills or motivation. The main challenges are not being well enough (93.8%), work making their condition worse (91.8%), barriers in the job market (86.3%), and fear of pressure from the benefits system (86.3%).

The benefits system creates its own barriers too.

Support is either not available for those who need it or is forced on those who do not. The system feels intimidating and impersonal, and sanctions create fear. This leads to distrust. Many people worry that getting support or trying out work could harm their benefits.

Support offered through Jobcentres does not meet disabled people’s needs.

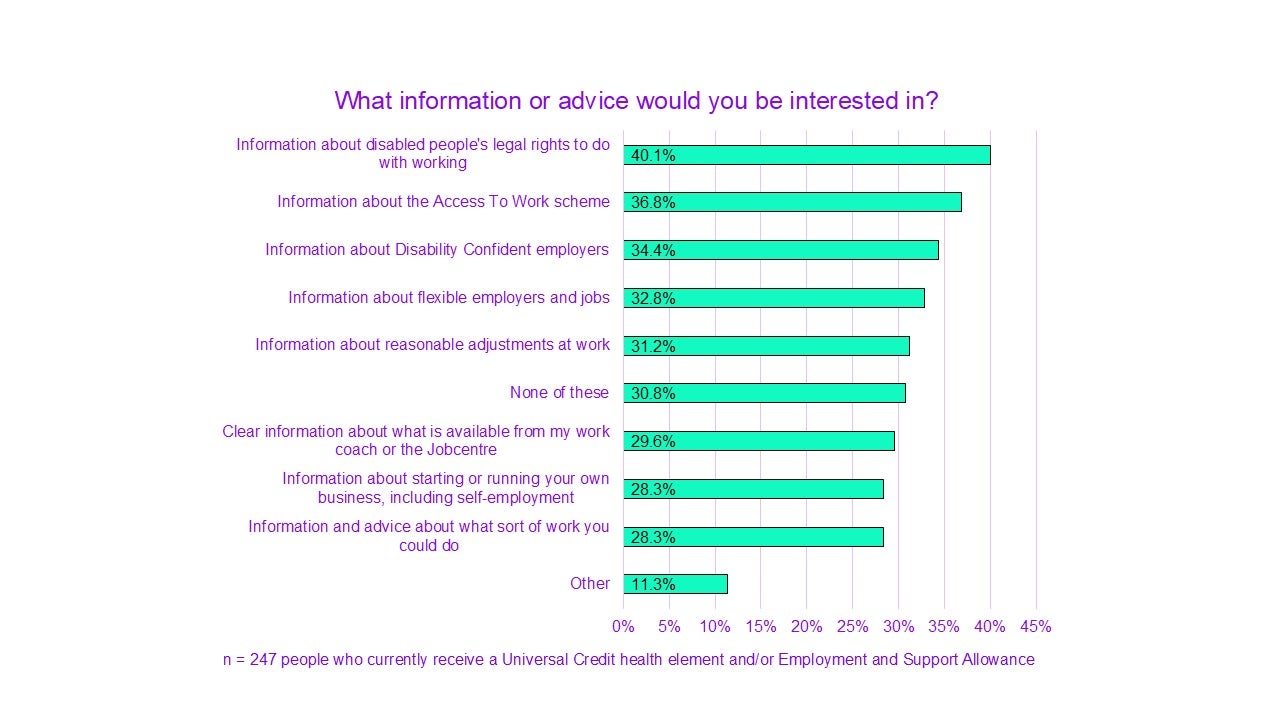

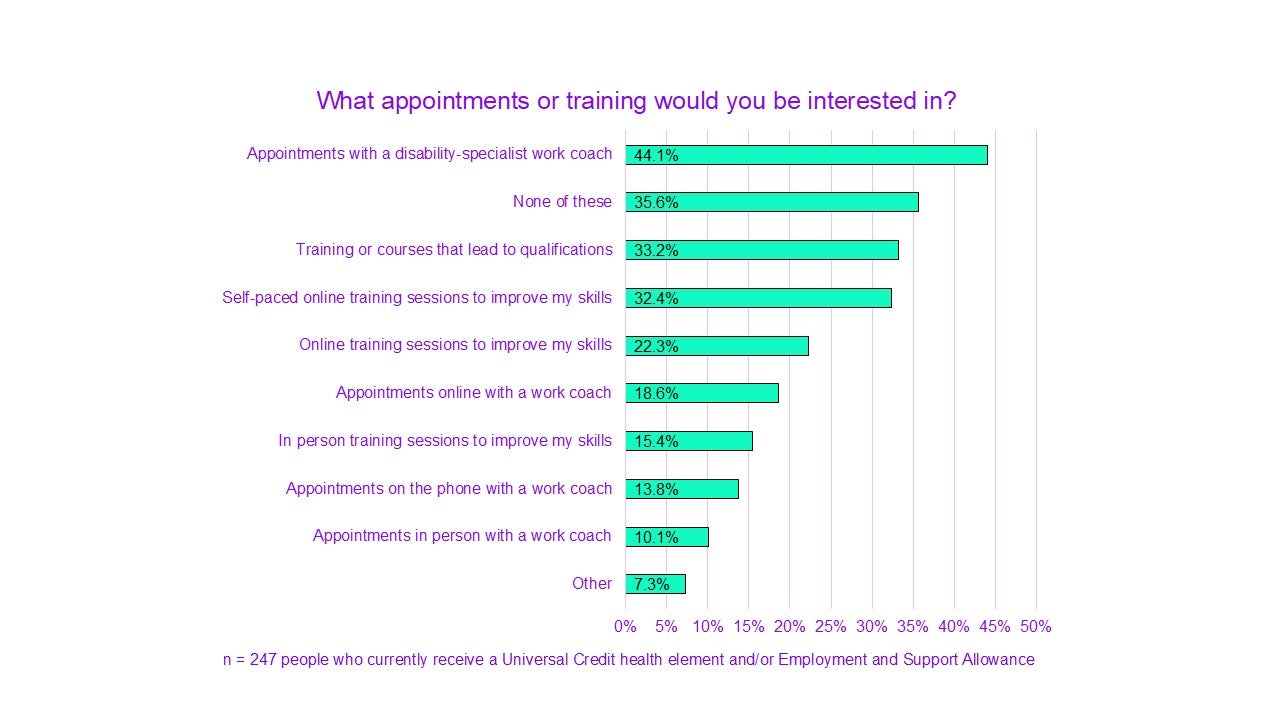

People are not given information they need. And training or support is often not accessible or relevant.

Disabled people fall or are pushed out of work when employers do not support them.

This means that many people could still do their job with adjustments, after a period of sick leave or with a role change. But they are not allowed to do so.

What needs to change?

We asked disabled people what they would like to change about the benefits system. They told us:

- More information and support is needed. This includes:

- finding suitable work opportunities and training courses

- offering more personalised support

- helping with adjustments

- making changes to Access to Work

- providing support while in work

- Staff should improve their knowledge of disability. This includes training and hiring more disabled employees.

- The process of trying out work must be risk free. This includes allowing a grace period and changing work restrictions.

- The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) needs to collaborate with employers. This will help improve conditions and address the lack of opportunities.

- Employers need to stop people falling out of work. Employers must:

- make adjustments

- offer appropriate sick leave

- improve flexible working options

- support disabled people if their needs change

- An empathetic approach is essential for support. It should be based on listening and respecting lived experience.

- There needs to be a shift away from a punitive culture. This involves reducing pressure and accepting people’s needs, barriers, and goals. Without the risk of sanctions.

- Support should be accessible and optional. Support must be easy to access, optional, and provide practical help with clear advice. This includes information about their legal rights at work.

- Communication and information must be clearer and more effective. This will help ensure that everyone understands their options and rights.

- We must stop the stigma that harms disabled people. This includes addressing the shaming faced by those who need to claim benefits.

- Trust should be restored through collaboration. Designing services with disabled people will help to rebuild trust and address the power imbalance.

Policy report

JRF have published a joint policy report, built on findings from this research. It puts forward some broader findings and policy recommendations.

We hope this research highlights the urgent need for change to the Government, policymakers, and everyone involved in the benefits system. Rebuilding our welfare system is essential, so that everyone who needs it is treated with kindness, respect, and trust.

Introduction

In recent decades, disability benefits have been a main target for UK government budget cuts. This focus appears to remain fairly stable across time and political parties. But we know that life costs significantly more if you’re disabled (Scope, 2023a; Scope, 2024a; WPI Economics, 2024). And that disability benefits often do not fully cover these costs (Scope, 2024a).

Another recent analysis has also revealed alarming levels of poverty among disabled claimants of Universal Credit. Most are in material deprivation. This means they do not have access to essential items and activities. And around half are experiencing food insecurity (JRF, 2024). This means their households had to reduce the amount, quality or variety of food. Such cuts can therefore be detrimental to many disabled people and their households.

Disabled people’s employment has been receiving much attention in political and public spheres. Many point to the lower rates of employment among disabled people as a major issue. This emphasis, however, tends to look for solutions within benefit budgets. It does not directly inspect employment barriers.

The repeated use of the concept of ‘economic inactivity’ in the context of disability benefits reflects a key issue. Supporting those in need is a moral obligation for every society. Social security or benefits are meant to serve this purpose. Yet instead of being a device to support those in need, this narrative positions disabled people in the context of a financial debt to national economy.

Some claimants of health-related Universal Credit or Employment and Support Allowance are already working. However, not everyone can move into work or work more. Crucially, no one should be forced to. Evidence suggests that many disabled people are interested in working (DWP, 2020). But they are not able to try or move into work for different reasons.

Disabled people’s employment rate is lower than non-disabled people’s employment rate. This measure, called the 'disability employment gap', has remained around 30% over the last decade (Scope, 2023b). Disabled people are also twice as likely to leave their work (Scope, 2023b).

For work to be sustainable, it needs to be secure. Measures of work security include reasonable and stable pay and access to rights and protection. It also includes contract-based commitments around the amount and future of people’s work. A recent report has revealed disabled people are 1.5 times more likely to be in severely insecure work compared to non-disabled workers (The Work Foundation, 2023). Insecure work means work without guaranteed hours or future work, like temporary or zero hour contracts. With unpredictable pay or pay too low to live on. Or without access to employment rights and protections.

Disabled workers from Black and Asian backgrounds have a slightly higher likelihood to be in insecure work. And being a disabled woman increases this likelihood to 2.2 times. A total of 1.3 million disabled workers are currently in severely insecure work in the UK. Another 430,000 disabled workers are underemployed. This means they are working, but would like to work more hours. (The Work Foundation, 2023).

All these facts demonstrate the imperative need for profound changes in the benefit system and the culture around it. Benefits should be stable and reliable. And they should provide accessible support for disabled people who wish to work.

The current and previous governments have suggested several potential proposals for reform (DWP, 2023). Some of these have, however, raised serious concerns among disabled people. Consultations with charities and disabled individuals took place before formal government policy proposals. But many feel the final proposals do not reflect people’s wishes or best interests.

Scope and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) have partnered for this current project. We wanted to offer disabled people the opportunity to respond to the new proposed changes and consider how they might affect them. As part of this, we also wanted to allow people to share their experiences of the benefits system more broadly. With this aim, we conducted a mixed methods research study to examine possible barriers and solutions to people's move into work.

Glossary

We will use some terms and abbreviations in this research to describe different parts of the benefit system.

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP)

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is a ministerial public service department. They are responsible for the benefits, pensions and child maintenance policy. They administer benefits and run Jobcentres. Benefit policy is decided by the government and enacted by the DWP.

Employment and Support Allowance (ESA)

If people cannot work because of disability, they might be able to claim New Style Employment and Support Allowance (ESA).

There are 2 types of ESA: New Style ESA, also called contributory ESA or contribution-based ESA, and income-based ESA. New claimants can only claim New Style ESA.

The 2 groups for ESA are the Work-Related Activity Group (WRAG) and the Support Group (SG).

People can be entitled to New Style ESA and Universal Credit at the same time. Although the ESA would count as income for somebody’s Universal Credit calculation.

Work-Related Activity Group (WRAG)

ESA claimants might be assessed to have limited capability for work.

People can only be in this group for 12 months, and will receive the lower amount of ESA.

People do not have to work, but a work coach may ask them to do some regular tasks to get ready for work. These tasks are called work-related requirements. And would be recorded as part of someone’s claimant commitments .

Support Group (SG)

ESA claimants might be assessed to have limited capability for work and work-related activity.

There is no time limit for the support group, and they will receive the higher amount of ESA.

People do not have to work or prepare for work.

The Equality Act 2010

The Equality Act 2010 says that discrimination is illegal. The Equality Act 2010 replaced the Disability Discrimination Act. It says that disabled people have the right to ‘reasonable adjustments’ that make jobs and services accessible to them. Access for disabled people is a legal requirement.

This applies to employers, public and private services. Some things such as transport are covered by specific regulations.

Extra costs

Life costs more for disabled people and their families, spending more on essential goods and services like; heating, insurance, equipment and therapies. These extra costs mean disabled people have less money in their pocket than non-disabled people, or go without.

The result is that disabled people are more likely to have a lower standard of living, even when they earn the same.

Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA)

If people are looking for work, they might be able to claim Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA).

There are 2 types of JSA: New Style JSA, also called contributory JSA or contribution-based JSA, and income-based JSA. New claimants can only claim New Style JSA. Income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance has been replaced by Universal Credit. People can be entitled to New Style JSA and Universal Credit at the same time.

Income Support

Income Support was a benefit for people on a low income who were not in full-time employment. And had other factors like disability, being a lone parent, or a carer. People cannot make a new claim for Income Support and now would claim Universal Credit instead.

Personal Independence Payment (PIP)

Personal Independence Payment (PIP) is a benefit for disabled people. It is meant to be for people who struggle with everyday tasks or mobility. This is designed to address the extra costs that disabled people face.

It is made of 2 components: the daily living component and the mobility component. People are assessed for their eligibility. It is not a means-tested benefit. People’s earnings, other income or savings do not affect this.

Reasonable adjustments

The Equality Act 2010 requires an employer to make reasonable adjustments to enable a disabled person to work.

People can get adjustments if they are or become disabled. Or if their condition or role at work changes.

People can ask for reasonable adjustments during recruitment or once they’ve started work. Many reasonable adjustments cost little or nothing. But they can make a big difference.

Universal Credit (UC)

is a means-tested benefit. This means it is for people on a low income and without significant savings.

Universal Credit has a standard allowance. People may be eligible for extra payments, known as elements. These are extra amounts for things like childcare or housing, or if people cannot work because of sickness or disability. The 2 health-related elements of UC are Limited Capability for Work (LCW) and Limited Capability for Work and Work-Related Activity (LCWRA).

Limited Capability for Work (LCW)

Universal Credit claimants might be assessed as having Limited Capability for Work. Someone with LCW does not have to work now, but needs to prepare to work in the future. You will not receive any more money if you’re in this group, if you claimed after 3 April 2017.

Limited Capability for Work and Work-Related Activity (LCWRA)

Universal Credit claimants might be assessed as having Limited Capability for Work and Work-Related Activity. People will not have to work or prepare for work. They receive extra money as well as the standard allowance.

Work Capability Assessment (WCA)

Work Capability Assessment (WCA) is the process where the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) decides if someone has limited capability for work or work-related activity. This is part of the claim process for a health-element of Universal Credit, or for Employment and Support Allowance.

This happens after someone’s doctor has provided a fit note. There is usually paperwork then an assessment appointment.

Work-related disability benefits

We will use work-related disability benefits to mean benefits disabled people of working age can claim from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). If their disability or health condition means they can’t work or it is harder for them to work.

When we refer to work-related disability benefits in this report, we mean Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) or the health-related elements of Universal Credit: Limited Capability for Work (LCW) and Limited Capability for Work and Work-Related Activity (LCWRA).

People are awarded work-related disability benefits after a Work Capability Assessment (WCA).

Accessibility statement

We use HemingwayApp to make sure our content has:

- a reading grade between 6 and 8 maximum

- no “very hard to read” sentences

Because of the topic of this report, there are some complex words that we cannot remove. This means the Hemingway algorithm shows a higher readability grade than what we would usually aim for. There are also some places where we’ve not been able to reduce very hard to read sentences.

We have still worked to make our content as accessible as possible. We focused on having:

- shorter paragraphs

- shorter sentences

- bullet points

- additional headings to help you navigate the content

- plain language where possible

About this research

Research objectives

We focused on the following questions:

What is disabled people’s current experience of claiming work-related disability benefits? To be able to understand the types of change most needed, and to adequately evaluate existing proposals, we first sought to explore people’s experiences of the current system.

We then moved on to focus on needed changes:

- How effective are current white paper (‘Transforming support: the health and disability white paper’. [2023]) and other related reform proposals at supporting people into work? What are potential issues with these proposals?

- What other changes would make the biggest difference to remove barriers and help disabled people into sustainable work?

- What changes would help remove the risk for disabled people who are interested in trying work or engaging with employment support?

- What changes to the work-related disability benefit system would improve people’s experience of the system and make it fairer?

What we did

To answer these questions, we used a mixed method approach across 5 stages:

- A survey about disabled people’s general experiences of claiming work-related disability benefits

- Discussion groups and interviews with people currently receiving health-related Universal Credit about their experiences and responses to main policy proposals

- A survey about assessments, disabled people’s engagement with employment support and barriers to work

- Deliberative workshop discussion groups with people currently receiving health-related Universal Credit about what they think would help and responses to developed policy proposals

- A survey to disabled people about policy proposals

We used data from each stage to inform the next one.

Fieldwork took place between February and July 2024.

Qualitative data from our groups and interviews was recorded and transcribed verbatim. We then analysed the data thematically. Thematic analysis is a method for identifying different patterns in the data. As part of this process, we used a deductive and an inductive approach to coding. Codes are patterns of meaning that we found in the data. This means that when looking at the data, we were guided both by some of the things we wanted to find out, and by things that participants raised.

All of the findings presented in this report have been made strictly anonymous.

Participants

A total of 921 participants from Scope’s Lived Experience Panel have taken part in the project (please see full details in the appendix). Each stage had a different number of participants, with some taking part in more than one stage.

Throughout this report, we use the term ‘disabled people’ to describe participants in this research. We used this term to mean people with an impairment, health condition, or access need. Participants in this research all identified as disabled using this definition or received a disability-related benefit.

Scope is a pan-disability charity that promotes the social model of disability. This means we believe people are disabled by barriers in society, not by their impairments or conditions. As part of this, we try to avoid using diagnostic labels when unnecessary.

Instead, we used broad impairment categories from Scope’s unified diversity monitoring questions. These were developed through a content design process which involved gathering best practice research. Then feedback from a diverse group of colleagues, volunteers, customers, and panellists.

Out of the total number of participants in the project, 382 were disabled people who currently receive Universal Credit (UC) with Limited Capability for Work (LCW) or Limited Capability for Work and Work-Related Activity (LCWRA) or Employment and Support Allowance (ESA). Participants’ age in this group ranged from 18 to over 65, and most were women (74.4%). The majority were White British (87.2%). 11.5% were employed (full-time, part-time, or self-employed) and another 10.5% were actively seeking employment.

Participants who currently receive UC, with LCW or LCWRA, or ESA had a broad range of impairment or condition categories (many identified as having more than one category):

| Category | Number | Percentage of group |

| Chronic or long-term condition | 265 | 69.37% |

| Mental health | 233 | 60.99% |

| Chronic or long-term pain | 221 | 57.85% |

| Mobility (moving around) | 246 | 64.40% |

| Neurodivergence (including autism, social or behavioural differences or ADHD) | 129 | 33.77% |

| Stamina, breathing or fatigue | 171 | 44.76% |

| Neurological condition (including epilepsy) | 109 | 28.53% |

| Learning, understanding or concentrating | 109 | 28.53% |

| Memory | 104 | 27.23% |

| Dexterity (handling or using objects) | 100 | 26.18% |

| Hearing | 52 | 13.61% |

| Speech or language | 29 | 7.59% |

| Vision | 39 | 10.21% |

A further 66 survey respondents over the whole project had gone through or said they were currently going through the Work Capability Assessment process. Some of these respondents said that they hadn’t had (61) or started (5) the WCA process when they first took part in the project, but had by the time the fieldwork ended. This means we spoke to 443 people who had interacted with the work-related disability benefits claim process.

Our first survey included a sample of 425 disabled people. 35.3% (n=150) of them currently receive Universal Credit with LCW or LCWRA or Employment and Support Allowance (ESA). And another 15.1% (n=64) have had a Work Capability Assessment (WCA) but are not currently claiming these benefits.

Our second survey included a sample of 527 disabled people. 46.9% (n=247) currently receive Universal Credit with LCW or LCWRA or Employment and Support Allowance (ESA). Another 15.7% (n=83) have had a Work Capability Assessment (WCA) but are not currently claiming these benefits.

Our third survey which focused on policy proposals, included a sample of 559 disabled people. 39.5% (n=221) currently receive Universal Credit with LCW or LCWRA or Employment and Support Allowance. Another 11.6% (n=48) had had or are going through a WCA. 78.7% (n=440) of respondents currently receive PIP.

In the first qualitative stage, we spoke with 16 participants who all receive Universal Credit with LCW or LCWRA (4 have LCW and 12 have LCWRA). They also received a number of other benefits and support, such as Personal Independence Payment (9 participants) and Council Tax Reduction (5 participants) and Employment and Support Allowance (1 participant).

Participants spread across impairment categories (many identified as having more than one category):

- 10 had a chronic or long term condition

- 9 had a mental health condition

- 9 had chronic or long-term pain

- 9 had a mobility impairment

- 7 identified themselves as being neurodivergent

- 6 selected stamina, breathing, or fatigue

- 4 selected a neurological condition (including epilepsy)

- 4 selected learning, understanding, or concentrating;

- 4 selected memory

- 4 selected dexterity

- 3 had hearing impairments

- 2 had impairments to do with speech or language

- 1 had a visual impairment

Throughout our report, when referring to participants impairments or conditions, we have only used terms based on participants’ self-descriptions.

Group participants’ age brackets ranged from 18 to 65.10 participants were women (4 were men, 2 preferred not to tell us). And the majority (15) were White British. Participants lived across England and Wales.

In terms of employment status, most (11) were unable to work due to illness or disability. 4 were employed (part-time or self-employed). 1 was a full-time student.

In the second qualitative stage, we spoke with 8 of these participants again.

Warning Content warning

This report discusses sensitive topics, including physical and mental health challenges, poverty, experiences of disability, assessment processes, distress, trauma, suicidal ideation and discrimination.

If you are affected by any of the content in this report, and want to speak to someone about it, please contact Scope's helpline on:

0808 800 3333.

If you need to contact someone urgently:

Call Samaritans on 116 123

Call Mind on 0300 123 3393

Text Shout on 85258

Work-related disability benefits

Universal Credit (UC)

Universal Credit (UC) is a means-tested benefit. This means it is based on a person’s income and savings. People may be eligible if they:

- are not working or are on a low income

- are under State Pension age

- do not have savings of £16,000 or more

Disabled people who have an illness or condition that affects their ability to work may also be eligible for “health-related” elements of Universal Credit. These are called “Limited Capability for Work” (LCW) or “Limited Capability for Work and Work-Related Activity” (LCWRA). These are awarded following a Work Capability Assessment (WCA). People may be given one of these elements depending on the outcome of this assessment.

Employment and Support Allowance (ESA)

Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) is another benefit that disabled people can receive.

There are 2 types of ESA:

- New Style ESA, also called contributory ESA or contribution-based ESA

- income-related ESA

If someone has not claimed ESA before, they can only claim New Style ESA.

New Style ESA eligibility depends on someone’s age, condition and income.

They must:

- be at least 16 and under State Pension age and

- have an illness or condition that affects their ability to work

They also must be one of the following:

- a part-time employee, working less than 16 hours a week

- previously an employee or self-employed person

- a full-time student

They also need 2 full years of National Insurance contributions out of the last 3 tax years.

Income-related ESA is a “legacy benefit” that can no longer be claimed. It has been replaced by Universal Credit for new claimants who are on a low income whose ability to work is affected by disability. Many people who claimed ESA in the past are still on ESA. And are still to be moved to Universal Credit.

The Work Capability Assessment (WCA) process

This report will relate to the process of the Work Capability Assessment (WCA) and the different terms that are part of it. Below is a description of the current WCA process for Universal Credit (UC) and Employment and Support Allowance (ESA).

A WCA is the process where the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) decides if you have limited capability for work or work-related activity. This happens after your doctor has provided a fit note. There is usually paperwork then an assessment appointment.

The assessment appointment focuses on disabled people’s ability to complete paid work or work-related activity. This is using limited measures of ability to work, like:

- being able to repeatedly move for 50 metres

- moving a light but bulky object such as an empty cardboard box

- reliably completing at least 2 tasks, one after the other

Claimants are put in different groups that have different levels of conditionality. Conditionality means work-related activities a claimant will have to do in order to keep their benefit.

There are 3 possible Work Capability Assessment outcomes:

- Being put in the “Limited Capability for Work and Work-Related Activity” (LCWRA) in Universal Credit or the “Support Group” (SG) for Employment and Support Allowance (ESA). There should be no conditionality and the maximum payment.

- Being put in the “Limited Capability for Work” (LCW) group in Universal Credit (UC) or the “Work Related Activity Group” (WRAG) for Employment and Support Allowance (ESA). There is less conditionality than standard UC or Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) and a lower payment compared to LCWRA.

- Being found “fit for work” and not being entitled to working-age disability benefits of ESA, LCWRA or LCW .This means you only receive standard Universal Credit or the legacy benefit Jobseeker’s Allowance.

Work and disability

Work can be different activities or tasks that are aimed at producing purpose, value or meaning. As a concept, work is not limited to being paid. Examples of this include care work, housework or administrative work that people have to complete. Similarly, work is not limited to a specific set of skills, tools or abilities. But in many social contexts, when people talk about work they tend to mean jobs that people are paid for.

People tend to value paid work more than other types of work that might have a bigger value to society or the environment. For example, volunteering or looking after your local area. The same is true for the context of the benefit system. This focus on paid work is particularly problematic for disabled people. This is because paid jobs seem to have significant barriers and consequences if they cannot be maintained (Scope, 2023b).

The following themes describe the values and experiences the disabled people we spoke with attached to work. This related to work in general, and to work in the context of benefits in particular.

Social views and attitudes towards work and disability

The meaning of work: motivated by the sense of worth associated with work, devalued by the lack of it

This theme describes people’s views on work, including their motivation and the values they associate with work. It also describes the way not being able to work negatively impacts some people. Scope’s position recognises not everyone can or should work, and does not view paid work as providing more value to individuals or society.

Throughout our discussions, people have frequently talked about work as something that defined a significant part of their self-worth. Beyond the obvious financial advantages, work was seen as something people derived meaning and a sense of purpose from. Although similar meaning could be obtained from non-paid work routes, paid work seemed to hold higher social value. It was seen as a marker of independence.

This feeling appeared to be stronger for those who previously had a job they appreciated or enjoyed. Those who managed to find suitable jobs described working as an empowering and motivating experience:

I'm coming to the end of a 6-month contract, doing some part-time work. This has been a great experience, a more positive reminder of my capability, rather than the LCWRA label. I would like to find more work to continue.

The ‘non-working’ or Limited Capability for Work and Work-Related Activity (LCWRA) label as mentioned here was mostly perceived more negatively. This sense of negative judgement about not being able to work often had a negative impact on people’s self-worth and self-esteem. Some people described experiencing grief over changes to their work-related capabilities. This was especially true for those who became disabled later in life or whose impairments had changed:

I was still struggling from losing my job because I had worked from being 15 years old. That was such a kick in the teeth. I’m actually still getting a lump in my throat when I think about it now.” “Definitely made me feel less than and useless. It all happened very suddenly for me. Seemed one day I was working, next day I was totally incapable.

As will be discussed later, the way the “limited capability for work” benefits are structured appear to leave no space for safely trying out work. This was challenging for those who felt they would be interested in doing some work if they were given the chance.

People highlighted their lack of control over some of these circumstances. They tended to describe not being able to work as an unfortunate position:

It's not a case of ‘I'm choosing not to work because I don't want to work’. I'm not choosing this. If you gave me the option, I would choose not to be like this.

Many were motivated but could not find paid work options to suit their access needs.

Some who have lost their jobs after becoming disabled were not used to living without work-related purpose. They were not able to work, but found no support for creating alternative goals. Or finding their individual path for meaning that is not dependent on financial income.

They described how living outside the paid work structure made them feel purposeless and unvalued:

It sounds a bit sad really, but I don't feel like I have much purpose. I get up in the morning because my carers just need me up, I don't get up in the morning because I've got things to do or places to be or anything like that. And everything's aimed at working people, so it's hard when you're at home all day and you know that your friends are out working or what have you. You, kind of, feel like you're not as valuable to society.

Volunteering

In contrast to paid work, those with volunteering experience talked about the many advantages this provided. They were able to contribute and take part in meaningful activities, but without the strict schedule or pressure of paid full-time work:

I do [do] quite a lot of voluntary. …But I can do it in my own time, and I've got nobody putting pressure on me at all. Nobody puts pressure on me. And to think that they could push me back into something where I've got to meet timescales and things like that.

Some disabled people we spoke with who were not volunteering expressed an interest in this option. As they thought it may be a more enabling option to explore their capabilities. But many had not explored this idea through fear of triggering a reassessment, and potentially being pushed into work because of it.

One participant told us she was moved to the Limited Capability for Work (LCW) after volunteering for a while. She previously had a LCWRA award. This meant she was no longer protected from activity requirements and her benefit payment was reduced. Although she had an understanding disability work coach who understood she was not yet ready for paid work, so was not pushed into paid work like others.

Viewed as a burden on employers

The view of disabled people being a burden on employers seemed very common. This was reflected in people’s experience in work and looking for work. Non-disabled job applicants appeared to be routinely favoured. Adjustments were often not offered or even considered. And people were forced out of their roles when they become disabled or when their condition deteriorates. People described a lack of enforcement of anti-discrimination and employment laws. As one participant mentioned regarding her previous work:

No one's ever discussed [reasonable adjustments]-, that's something I've never had said to me.

This was also freely expressed in various types of public discussions and social media that people were exposed to:

We're too much trouble, disabled people. Somebody actually said that on a post, you know, and he said, 'As a businessman, I wouldn't employ disabled people because they're never at work. I'd have to make too many allowances for them’.

Being aware of this view, people were trying to navigate such discriminatory behaviours. This sometimes meant considering hiding their impairment or condition if they could:

…I think when, you know, with like my occupational therapist, when we talk about moving into work and whatnot she literally says, 'Don't put on the CV, don't say anything that you're disabled until you've got your foot in the door at the interview.' And I think that's really sad because it's almost like you're made to feel bad about, like, any condition you have or a disability, and that's not right. I think a lot of people are willing to go to work and want to, but it's just finding that support base.

Stigma about receiving benefits

People described encountering misinformed and dismissive attitudes around their work-related activities. At the same time, they felt an intense social pressure to move into work. Their experiences reflected a widespread lack of understanding about disability and work. Despite this, judging whether disabled people 'deserve' their benefits seemed socially acceptable. Disabled people identified the news media and social media as consistently reinforcing this practice and stigma. This adds stress to disabled people's lives:

I mean, I've got broad shoulders, you can't say anything to me about being on benefits that I haven't heard before. But I know a lot of people do get really, really stressed with it.

Many therefore seemed to feel a constant need to explain or justify their benefit claiming. They tried to counter the common stigma of disabled people being ‘lazy’ and attempting to avoid work:

I think what people don't realise with people like me, and there's a lot of us, that if we could do something we would be still doing it. We wouldn't just be putting anything off.

People felt their claiming status made others view them as ‘second-class’ citizens. Within the benefit system, the Work Capability Assessment (WCA) process has reinforced that feeling. Rather than their right, benefits appear to be viewed as something to be ‘earned’

I know I'm not fit for work but being told it again and again and again is quite draining, and quite knocking to your confidence because you kind of feel like-, they kind of treat you like you're a number and you feel like you're not worthy of the benefit sometimes because they say ‘It's for people who work; Universal Credit is better for people who work, and you don't work’.

People also felt pressure to move into employment before they were ready. Political and media rhetoric about getting people back into work seemed to contribute greatly to this pressure:

I was worried about what would happen if I couldn't work, but I wanted to work because the government are constantly saying they want people to work, 'Get back to work, get back to work.' So I thought I would try it, but it didn't work for me.

A culture of suspicion

People felt a disproportionate public focus being placed on cases of benefit fraud. Efforts to expose such cases are part of the public discourse. This leads many to associate disabled people with potentially fraudulent, criminal behaviour. This seemed to be powered by direct public communications from the DWP and ministers. Similar statements are then used by other politicians and discussions on television and social media.

This narrative often caused people to feel persecuted, surveilled and threatened:

They don't realise what they do to us every time they spout some sort of rubbish against us. You know, we're fragile people, some of us. We don't need half the country coming on attack after us just because you say they should do.

There was a sense of these threatening messages and society’s distrust of disabled people becoming worse over time:

To me, they will want to know the ins and outs of my bank account in a minute because that's what you keep hearing on the news, is that the DWP now want access to your bank account, so they can look to see if you're actually fiddling the system. I'm like, ‘You can't do that. Where have our human rights gone? You know, our equality, our diversity?’ I just feel like, I don't know, you don't know who to go to. There's no trust anymore.

It has also been pointed out that official benefit fraud statistics tend to be far lower than common rhetoric would suggest (less than 3% for all benefits, see DWP, 2024a).

Some have felt that the true numbers are not getting enough attention:

I'm not denying that benefit fraud happens because we know it happens. But then when the DWP report the overall figures for benefit fraud, and it includes mistakes they've made, then you, kind of, see that it's not as many that are committing fraud as they'd like you to think.

The existence of a prominent National Benefit Fraud Hotline felt like it could expose disabled people to abuse. One of our participants described how someone she had a personal quarrel with had used the line to falsely report her. This resulted in her account being immediately frozen.

Claiming work-related disability benefits

The next few sections describe the findings on people’s experiences of the work-related benefit system. This includes various stages in people’s claiming process:

- the circumstances that led people to claim

- awareness and access to information before claiming

- experiences of the Work Capability Assessment itself

- experiences of engagement with the Jobcentre as current claimants, including barriers around moving into work

It is important to note that in recent years, the DWP monitors customer satisfaction through its Customer Experience Survey (CES). Some of the survey items included in the CES are parallel or similar to the ones included in our research. Its recent (as well as previous) results (DWP, 2024b) are often in considerable conflict with the ones presented in this report.

This may be due to several reasons. Crucially, the CES relied on a sample of claimants who have had contact with DWP during the last 3-month quarter for certain purposes. This may mean their sample is more likely to exclude those who have less frequent or no contact with the DWP. As we will see later, this is unlike the majority of people in our sample.

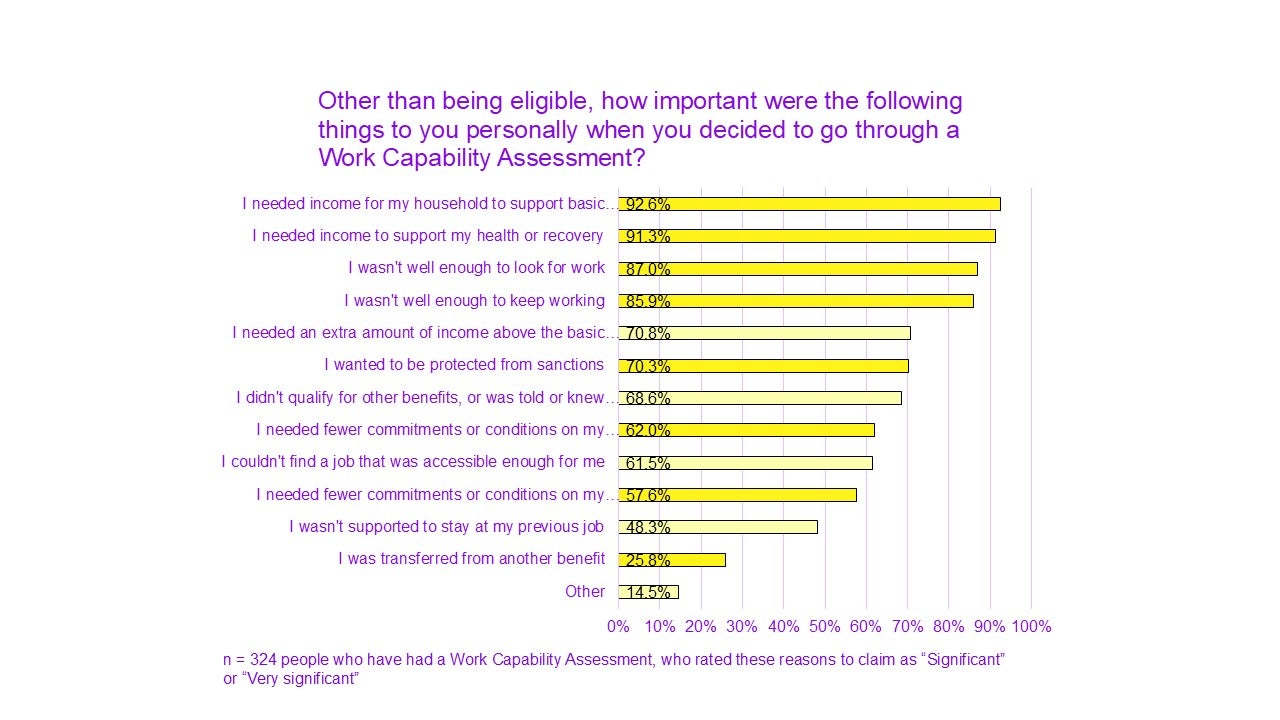

Reasons to claim

We asked people about different reasons that led them to claim work-related disability benefits. We also asked about how important each of them was to them personally.

Financial need: covering living costs, allowing time to recover

Financial need was the leading reason for people claiming work-related disability benefits. Not being able to work meant people struggled to cover their basic living essentials.

Combined with constantly increasing living costs, people found themselves needing financial support to be able to take care of themselves and their households. This motivation was more often based on general need rather than knowledge of possible payment amounts.

While the benefit amount often failed to meet their needs, it helped regain some stability and time to focus on their health:

It just felt like it gave me some time and that I could take a breath, just to be, like, okay, now I can focus on getting my health better rather than actually focusing on fighting, ‘Oh can I keep a job?, can I afford to do this?, can I do this?, can I do this?' You know, each week and just not knowing.

Some of the people we spoke with also claimed Personal Independence Payment (PIP), which is meant to cover the extra cost of disability. But we know this is not always the case.

The extra costs or ‘Disability Price Tag’ for a disabled household is £1,010 a month, after benefits have been taken into account (Scope, 2024a). This figure represents the extra costs disabled households face to attain the same standard of living as non-disabled households. So for those who were also unable to work or find appropriate work, the additional LCWRA element of Universal Credit (UC) provided much needed help.

One participant lost her teaching job after she became disabled. She described how being housebound and unable to work meant her expenses increased even more:

…I live alone, I have carers. My cost of living is higher than most people because you see I'm on oxygen, so my electricity is a lot higher. I have a lot of aids that are run by electricity, so my bills are a lot higher than the average person. So yes, the impact [of not having the award] would be huge.

Health reasons: too ill to work, keep working or look for work

Unsurprisingly, health considerations were one of the most common reasons for claiming work-related disability benefits. This included:

- those who have always had a condition or impairment that made it difficult to work

- those whose health or condition deteriorated

- those who became disabled at a certain point in their lives and had to stop working.

Similarly, this was either a gradual process or a sudden change. Sometimes it was the activities surrounding work that also made it harder, like using transport:

I had to get a bus, yes. That was not too bad. I wasn't as severely disabled as I am now but my back was going and I didn't know how bad it was until after getting the bus several mornings, I realised, no, I couldn't cope with this so I ended up getting a lift from a work colleague, who could see I was struggling. But I just wanted to prove to myself that I could work, but it didn't work.

Some had experienced more complex symptoms or complicated processes to receive their diagnoses. This has made their claiming journey longer and more difficult.

For me, I went onto Universal Credit because I was starting to not be able to work because of my disabilities and that and I hadn't had a diagnosis yet but I was in so much pain.

For those with acquired impairments, many described the shock of suddenly not being able to work. There was a long process of understanding and accepting their new situation while trying to learn about their rights.

Many described the challenge of trying to figure out their work-related capability. This could be because their condition was fluctuating or they were still learning their limitations. They also had to manage their condition and the admin burden of disability at the same time.

Loss of work: forced out or made redundant

Some have mentioned being made to leave their jobs when they became disabled or when their conditions became worse. For some this has been made clear by employers who no longer saw them as acceptable employees. For others, it has been a more gradual process. Mentions included public and private sector jobs, and none were offered adjustments to be able to stay in their roles.

This was a particularly difficult time for many, as they were trying to manage their health and were unaware of their rights:

He said, 'Voluntary redundancy. If you apply for voluntary redundancy then we'll accept it'. And my big boss even said to me in that meeting, and I can't actually believe somebody in such a position of power could utter these words. But, at the time, because I didn't know any different and I didn't know about disability rights or anything like that. I certainly do now, it's my day-to-day.

For many, this also meant becoming familiar with the benefit system for the first time:

I basically lost my job because of my health and then I started claiming Universal Credit and I didn't really know about what else I could, like, claim on top of that or what I was entitled to.

Information about benefits

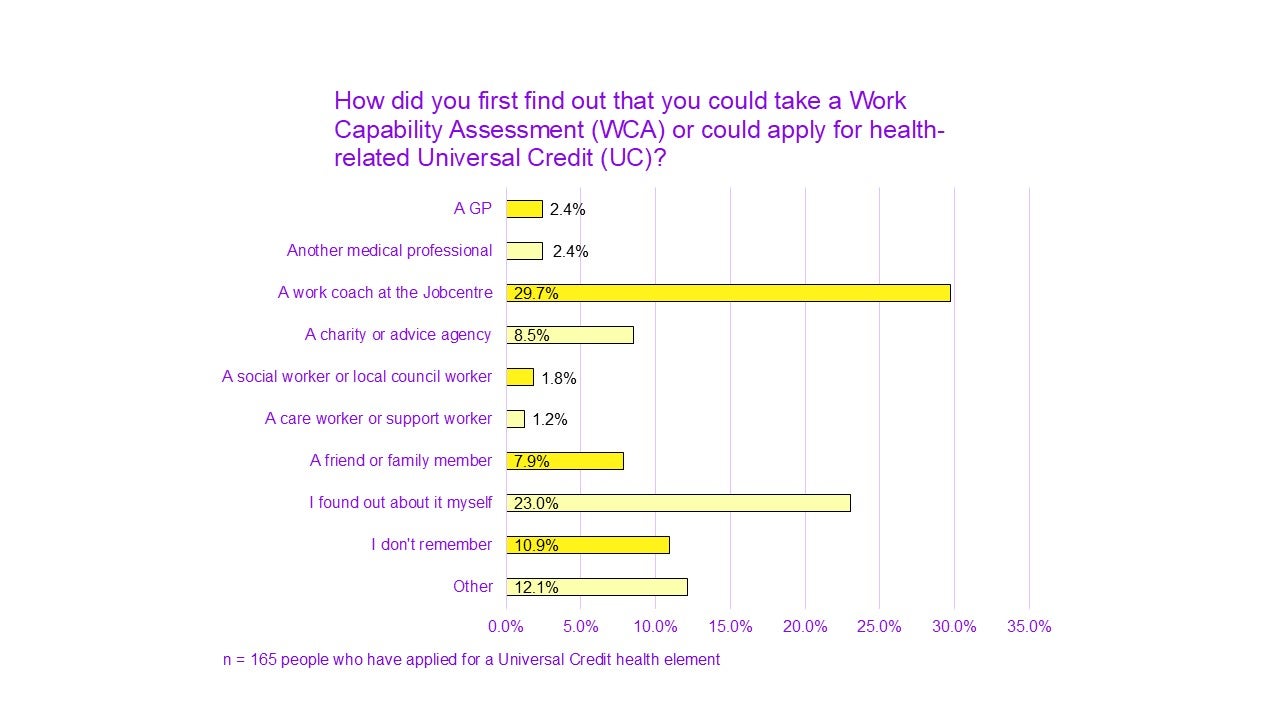

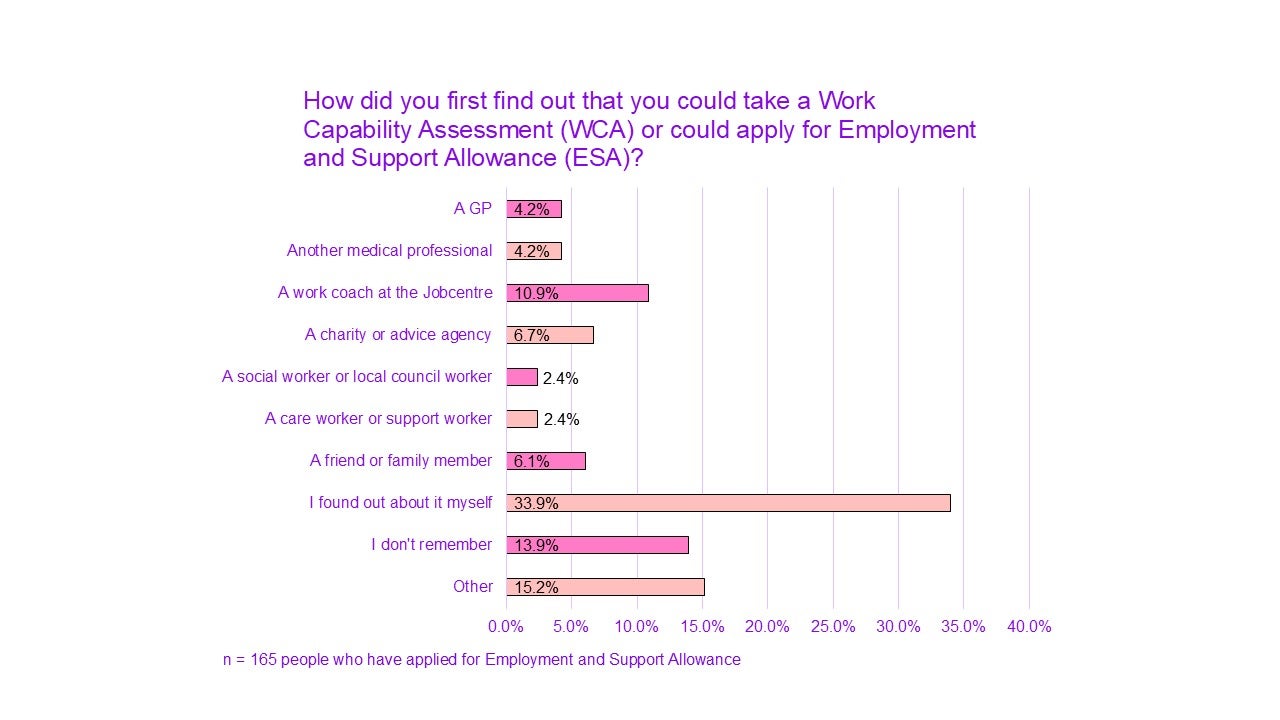

Where people get information and advice

People have mentioned learning about applying for benefits and receiving advice from different sources.

For those on Universal Credit (UC), 30% found out through a work coach at the Jobcentre. For those on ESA, only 11% through a work coach.

Some of the people we spoke to who had been advised by work coaches to take the WCA said this happened when work coaches noticed their access needs:

To be honest, I didn't even know that there was this Work Related [benefit], so I was just using Universal Credit as a top-up. And then, when I couldn't work I was just on Universal Credit and that's when my coach suggested it. So, I'm very lucky that I had a very good Work Coach because he saw I needed it and I didn't know that I could have that.

In some cases people did not seem to be proactively made aware of the possibility of claiming work-related disability benefits.

Most had to learn about their claiming options when they were already struggling with their health and finances. Some only found out about it coincidentally or when others mentioned it to them:

It was a long process because I didn't realise I should have been on it because I didn't receive sick pay when I should have to begin with. So, I had to chase it up. And then, when it came to that process we only realised by accident that I should have been receiving extra benefits. So, it was definitely a delayed process.

Many people have told us they struggled to find information about the benefits they were entitled to. Some have tried to receive information at the Jobcentre but were misdirected or dismissed:

And I had a bit of a long fight with the Jobcentre about different benefits that I may or may not be[...] suitable for. But they didn't ever really actually suggest that and it was a friend of mine that actually said, 'Oh, I've got Limited Capability and you should ask the Jobcentre about it.' And I think, like, it literally took a year before I was able to actually get anything properly progressed from the Jobcentre because everyone seemed to think it wasn't relevant to me or my situation was different, 'Oh, no. That's not quite right for you.' So, I think I wasn't really provided with any information about that and I, kind of, had to do it all off my own back and find out about it from a friend and Citizens Advice.

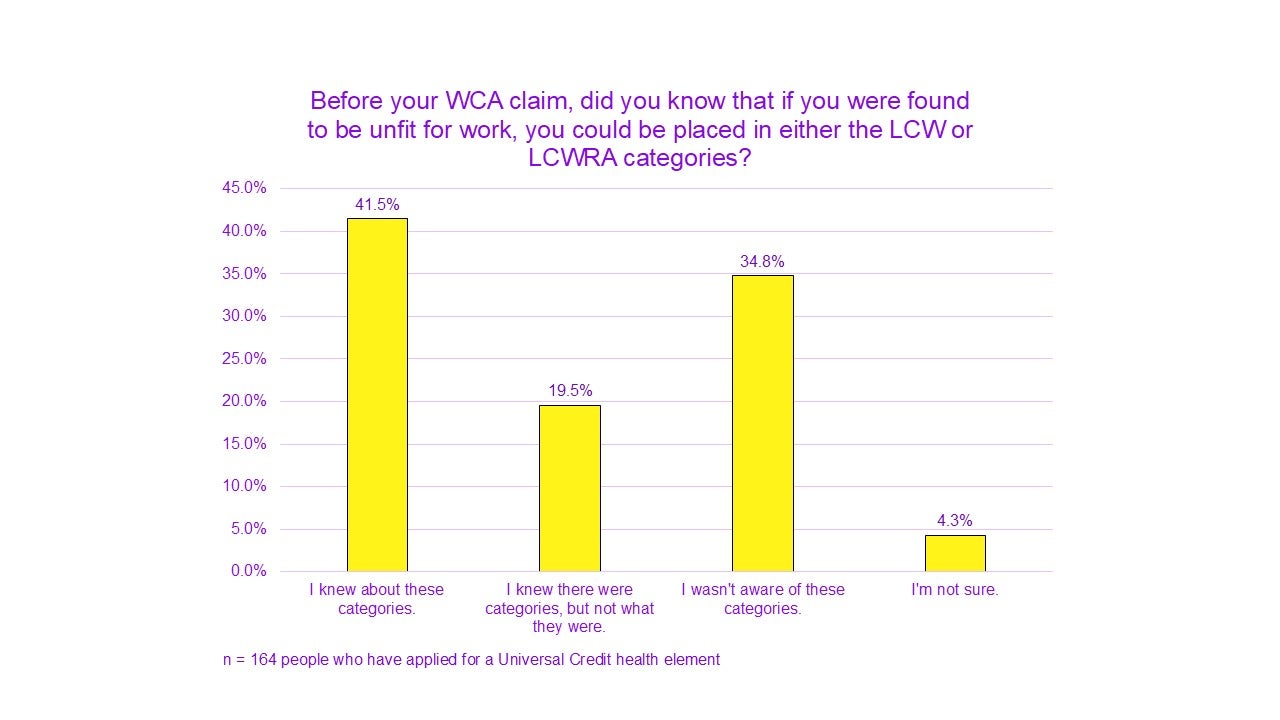

Low awareness of the Work Capability Assessment process and its details

Similar to eligibility, many claimants did not have clear information about the process before applying. Many started their journey not knowing what to expect. This included details about:

- the initial claiming paperwork

- the assessment appointment

- the possible outcomes and grouping following the decision

- the different conditions for each group

Some explained they were only directed to the general option of applying, and not provided with additional information:

I knew nothing. I didn't even know that it would be a bit of extra for me. I was just told, 'You need to go and do this. It'll take the place of your Universal Credit.' And I did it and, yes, I'm getting more from it than I did from my Universal Credit because then I didn't have to now work anymore because I can't. So, it was much better for me but I really didn't know what to expect at all.

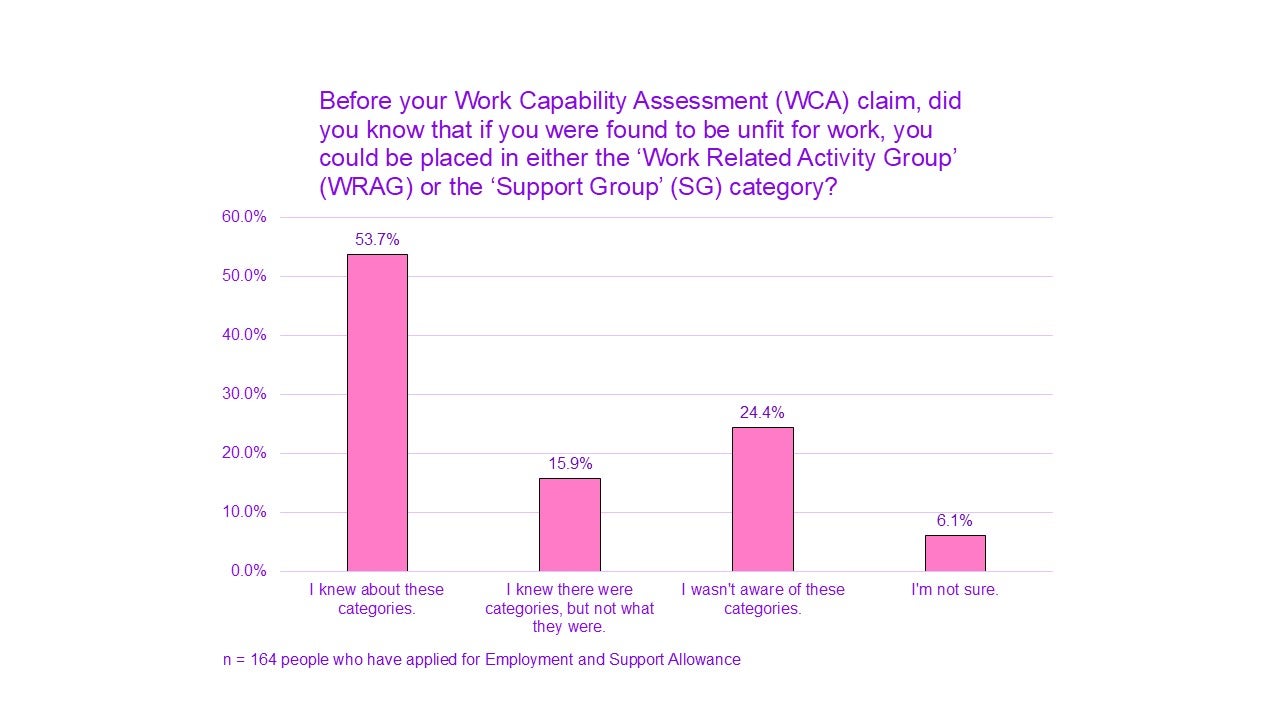

We found that many people who are currently claiming work-related benefits did not know about the possible outcome options or did not understand their impact before claiming. Only around 42% of people applying for UC and 54% of people applying for ESA knew about the categories they could be put in if they were found to have limited capability for work.

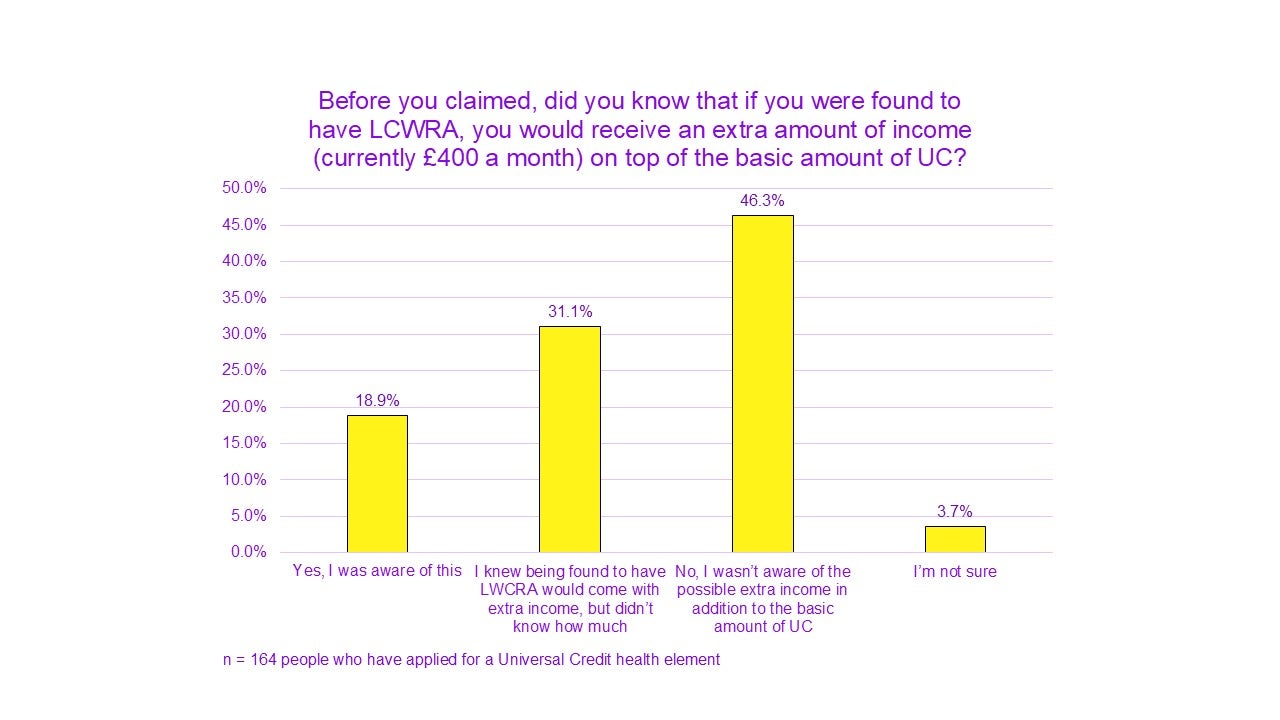

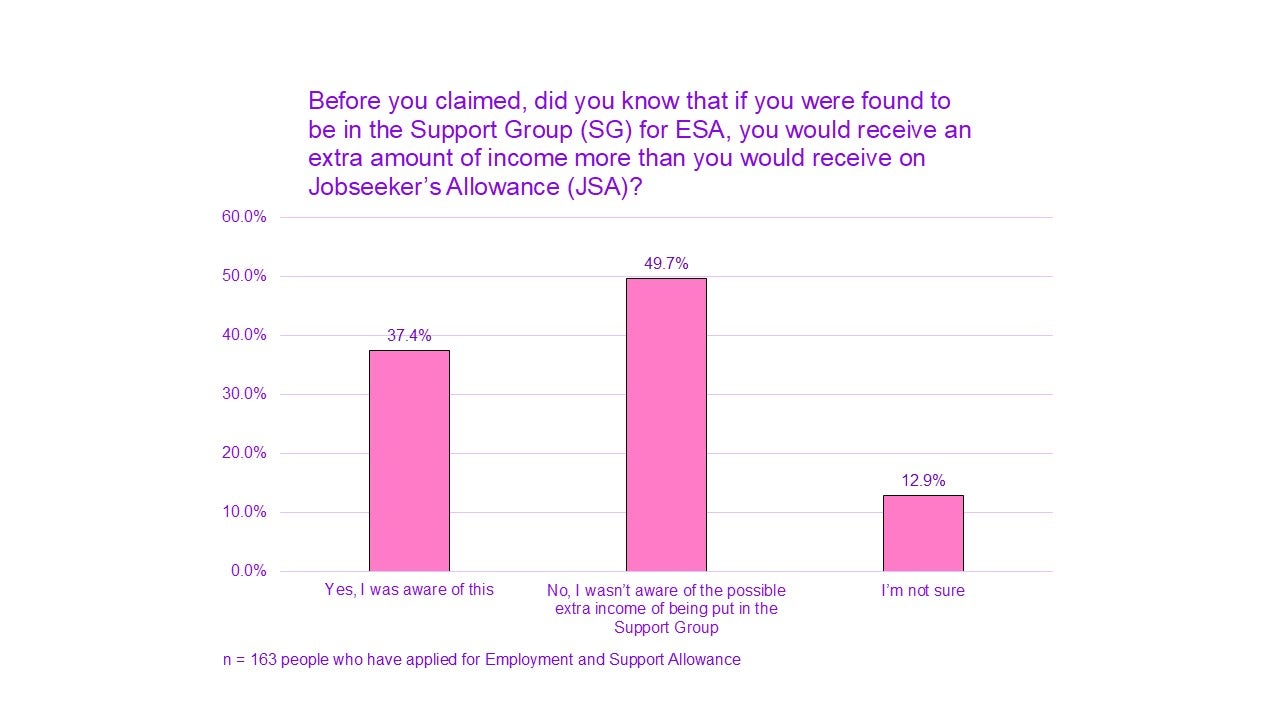

46% of people applying for UC and 50% of people applying for ESA said they weren’t aware of the possible extra income if they were put in the Limited Capability for Work and Work-Related Activity (LCWRA) or Support Group.

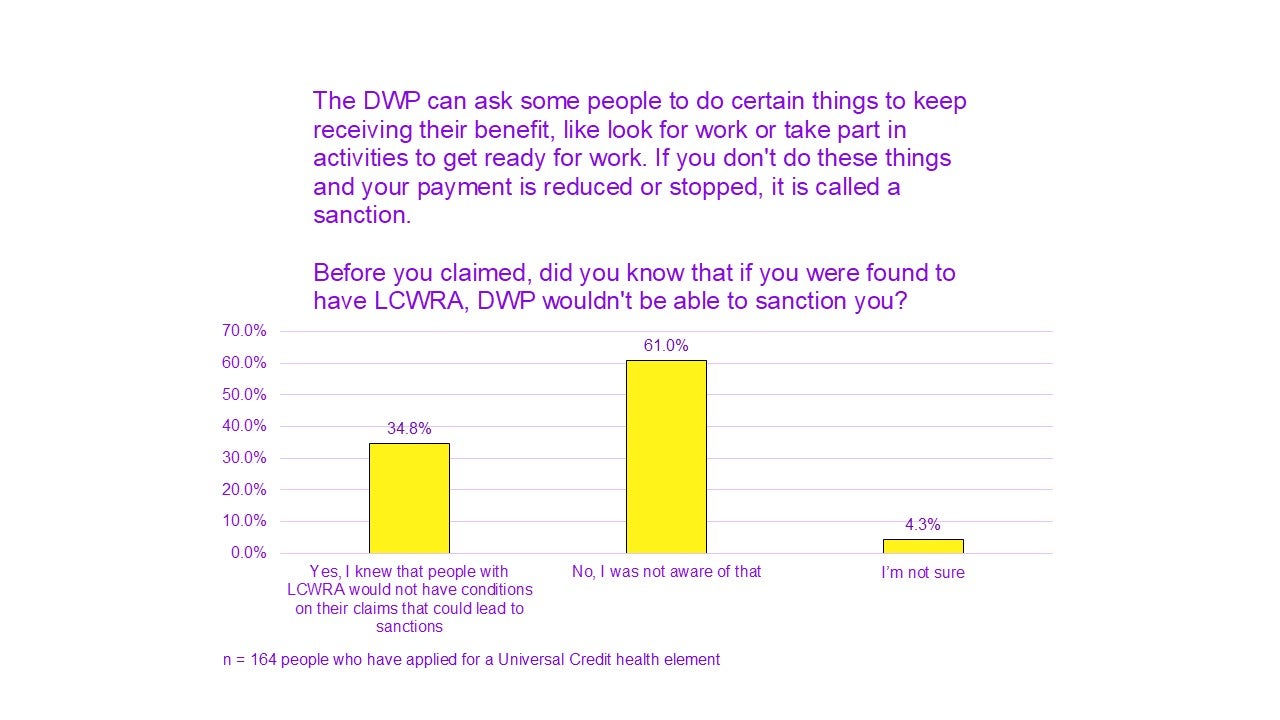

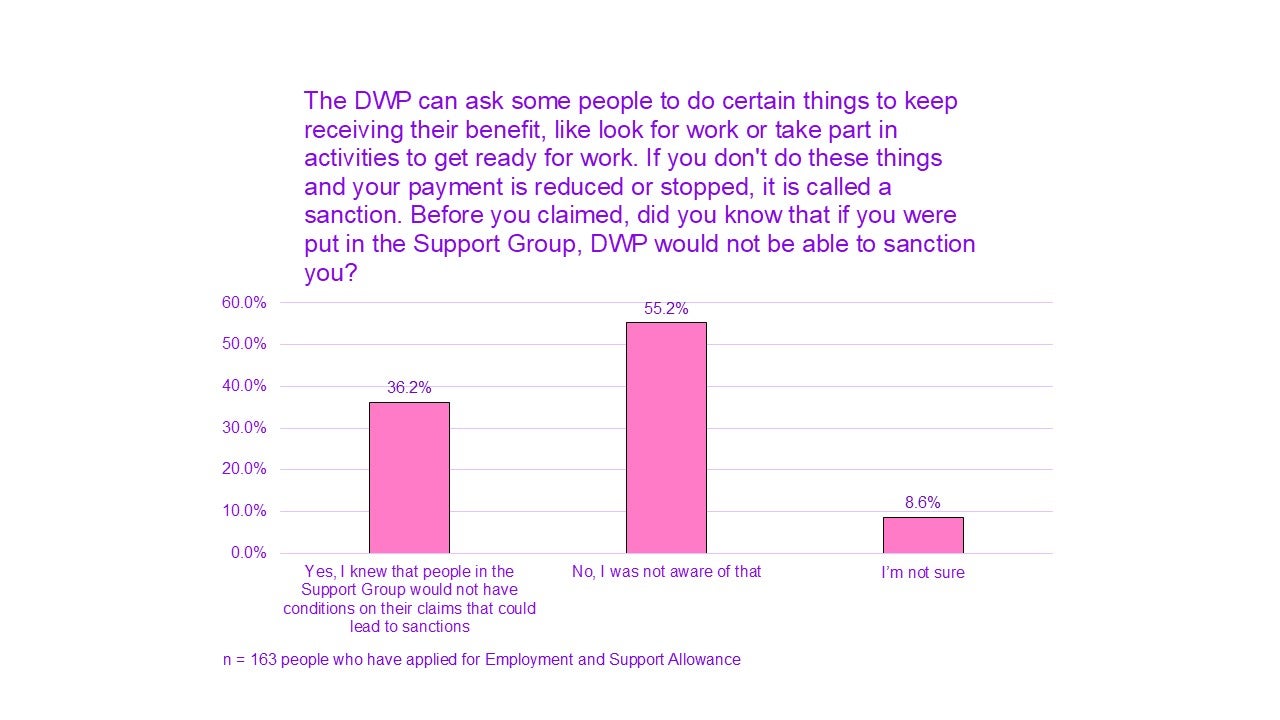

Before claiming, 61% of UC and 55% of ESA applicants were not aware of what the different groups meant in terms of possible conditions and sanctions.

Assessment experiences

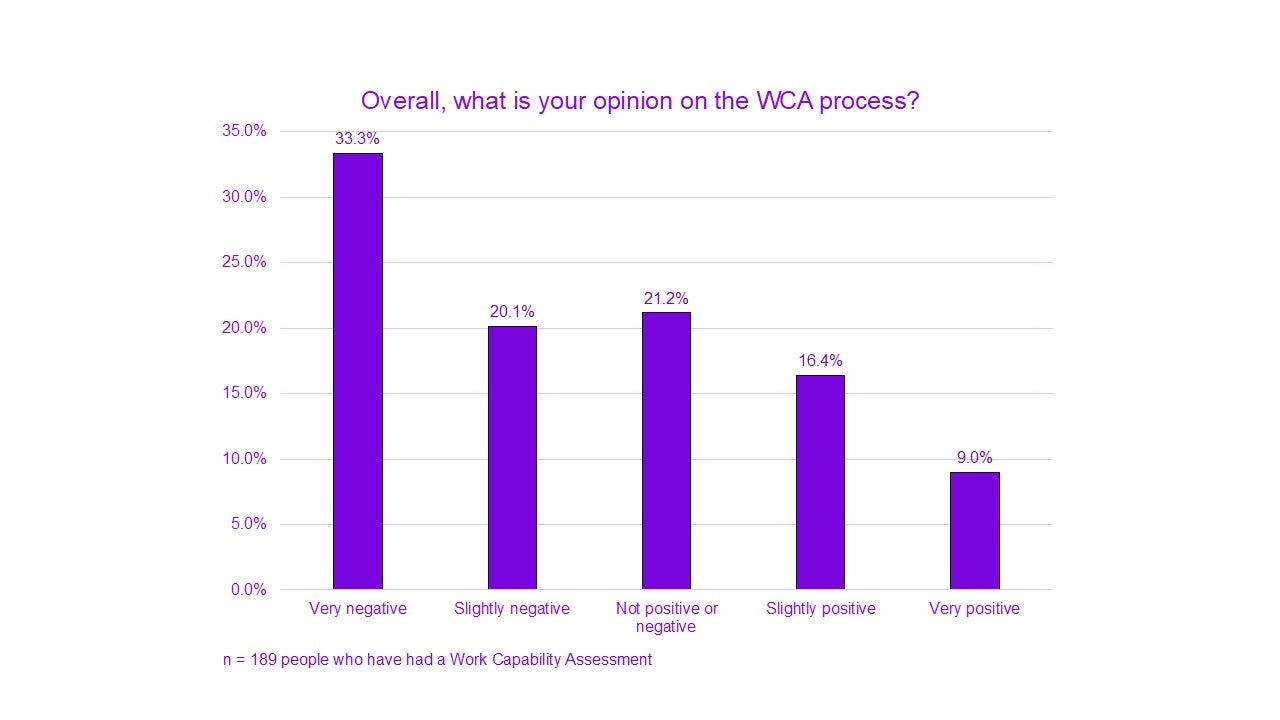

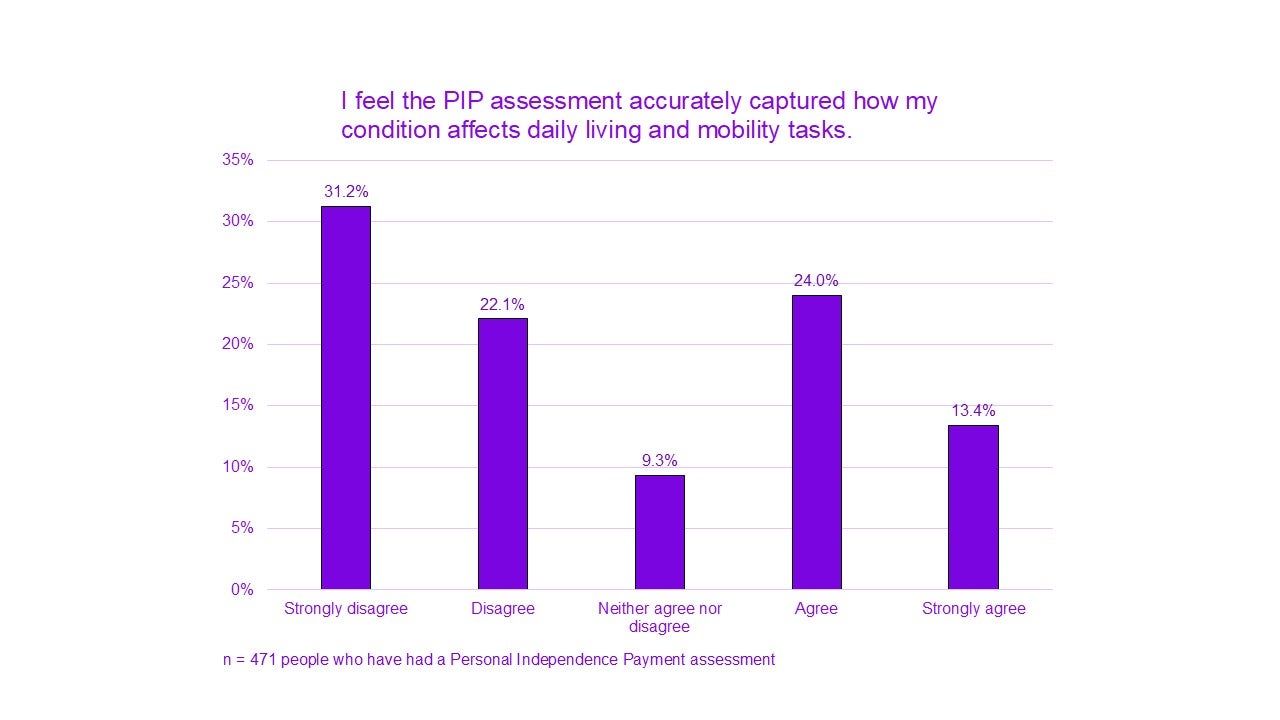

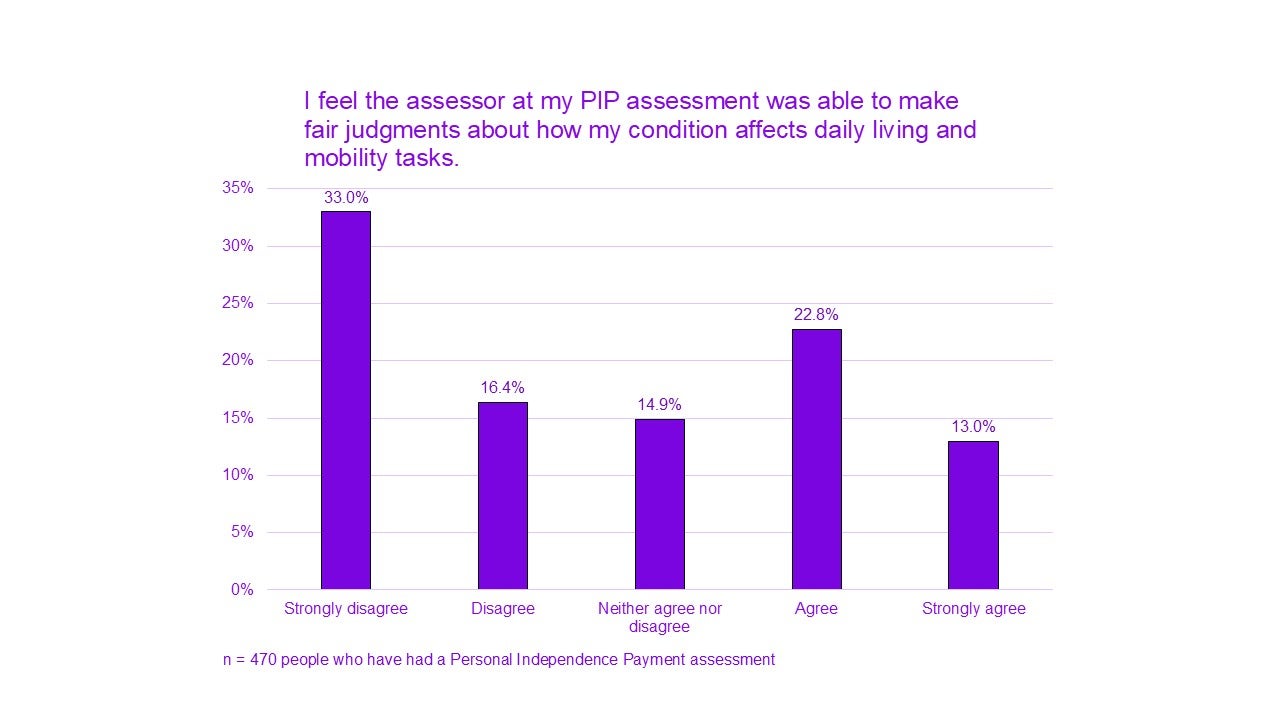

This section relates to people’s experiences at their assessment appointment. People’s overall opinions were more negative than positive, both in our discussions and on our surveys. Some have had a positive experience and felt lucky to have their needs acknowledged and validated. However, negative experiences were considerably more common. Some explained that although their assessment was straightforward, its emotional impact was still negative.

Unfit for purpose: a flawed structure

Inaccurate and unfair

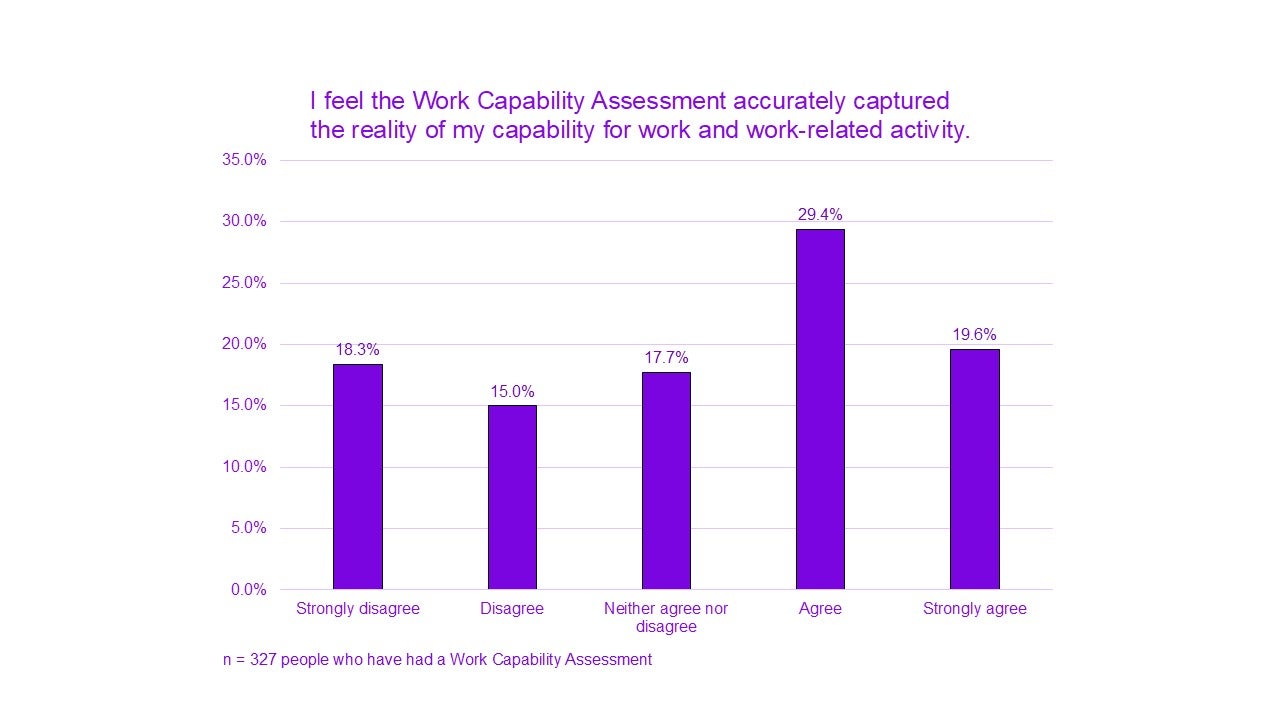

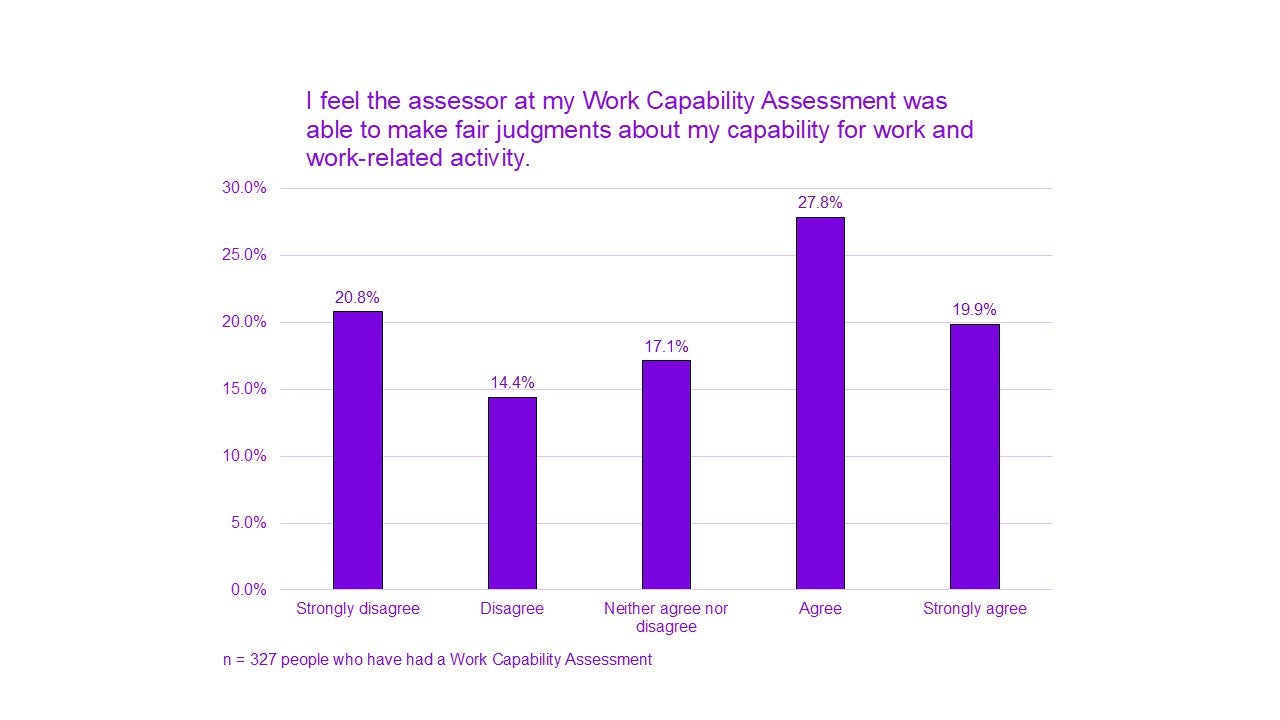

Less than half (49%) of survey respondents felt the Work Capability Assessment (WCA) accurately captured the reality of their capability for work and work-related activities. A similar proportion (48%) felt the assessor at their WCA was able to make fair judgements on their capability for work and work-related activities.

Assessors’ lack of knowledge in disability and access needs was obvious in many people’s experiences. This seemed to lead to superficial, inaccurate or simply wrong judgements about their capability:

It's quite hard, really, it's quite a hard thing to go through. It's difficult for somebody like myself, because we're, kind of, able-bodied, and obviously I can converse, everything is okay in that way, but quite often though, when you go for the assessment, they don't understand blindness and hearing impairments.” “…it's being assessed by someone who sometimes doesn't even know what your condition is, they literally said, 'I've never heard of that condition.' It's like, 'Okay, so how can you assess the validity of my claim if you've never heard of my conditions?

Inaccessible process and appointments

Many have shared finding different elements of the WCA process difficult. Sometimes it was nearly impossible. This was due to accessibility not being considered for the various stages of the process.

Several people have mentioned the capability for work questionnaire (UC50 or ESA50) to be extremely lengthy and confusing. They said they had to seek help for completing them. People said they were not offered help completing these questionnaires at the Jobcentre. Some have mentioned that when they asked for help, they were told it was not available:

I did try and ask the Jobcentre if they had someone in there that could help me fill out the forms because I really struggled with that and they said, 'Oh, no. We can't do that. That's not something we help with. You'll have to find someone else to help you, like a friend or family member.'

Indeed, people described getting help from Citizens Advice Bureau, friends or family instead.

The phrasing and focus of the questionnaire did not accurately capture the impact and barriers of many conditions and impairments, as one participant explained:

The questions are not phrased in a way suitable for mental or physical stuff, e.g. ADHD, autism, osteoarthritis, all fluctuating conditions impacting on our ability all the time, and you are asked to bring medications and physio stuff like squeezy balls etc.

Some have also mentioned struggling or not being able to access:

- information about the assessment appointment (including directions on how to get to the assessment centre)

- the assessment centre itself (the environment, building, and the room)

- requests made by assessors as part of the assessment

For example, one participant is legally blind and has a hearing impairment. She shared feeling lost when no adjustments were made to aid her in finding her way at the location of the assessment. She was also called to the room verbally only and was shown things physically on a screen and asked to sign it.

This lack of accessibility was also sometimes used against claimants. This was the case for the following participant whose assessment was held in a room with a door not wide enough to fit her wheelchair:

My very first assessment was in a room that wasn't even wide enough for my wheelchair. I had to close my wheelchair down and go through the door. So, of course, that went against me straight away. But that's not my fault that the door wasn't wide enough. She reported that I didn't look dizzy.

A slow and lengthy process

Although most were accepting of this reality, for many, the WCA claiming process took several months. The process was even longer for those who:

- were unwell (spending some or much of their time in the hospital)

- awaiting diagnosis

- had to appeal on their assessment’s decisions

This was at a time where they had no income from work, or their previous work income was stopped suddenly due to the changes in their health situation.

People having to request Mandatory Reconsiderations (where decisions are reviewed) or challenging the benefit decision at a tribunal adds significant delay.

It takes too long to get through to DWP to get forms, complete them, then the assessments and correct decisions.

Our discussions were focused on current claimants. This means the people we spoke to in depth all eventually managed to receive an award of health-related Universal Credit. But the lack of timely systemic protection for those who need it can cause real harm.

A discouraging and degrading experience

For many people, the timing of the assessment often found them in a particularly sensitive point. Many people were uncertain and anxious about their future and their capabilities. Some were still grieving over the changes to their health. The lack of informed expectations seemed to contribute to people’s worries and fears ahead of their assessment.

The assessment situation placed people in a highly vulnerable position. Claimants found themselves powerless in front of assessors. These judgements determined a meaningful part of their future. But assessors had no personal knowledge of them and their needs. There was also a sense that assessors were trying to challenge people’s barriers and symptoms, to be able to deny or reduce their eligibility.

The assessment seemed to focus solely on restrictions, rather than skills, abilities or potential. People said this forced a grim outlook on the future and on people’s worth. This was experienced as damaging to people’s self-esteem. It was also counterproductive to their potential future work prospects.

It, kind of, confirms the disability in the sense that you have the restriction, so it's going to be a lot harder for you to do anything in that way. I think it makes you think so much more about the process of working, in the sense of just applying for jobs and stipulating your disability in the sense of, will employers see this and then not want to employ you at all? Because you have this limitation. Definitely, I think it does impact your mental health as well with the anxiety towards it all.

Many have said they faced cold, uncompassionate and harsh treatment by their assessors. Some cases reached abusive levels:

I was able to walk very short distances with a stick and I was using a mobility scooter. The assessor picked up my stick and moved it to the other side of the room and said, 'Go and get your stick.' Not, 'Please-,' 'Go and get your stick,' and told me to get up without using the arms of the chair or holding on to the desk in front of me and I said, 'I'm not going to be able to do that,' and she said, 'No, go on. Do it.' I must have been about 25/26 at the time. I was in tears. It was 45 minutes in there. She wanted me also-, I've got PTSD and she asked me why I had PTSD. She wanted me to detail why I had PTSD and I said to her, 'That's not appropriate,' and then she said, 'Everything is appropriate in this room.' Utterly abusive and humiliating, and I was in tears, and when she opened the room she shouted, 'I'm sure you'll get what you want.'

Many described leaving the assessment in tears. They referred to their experience as traumatic or shared this experience led to a difficult period in terms of their mental health:

'I found it a really traumatic experience, the whole process broke me a bit.

For some, assessment decisions have had a long-term impact:

I knew I couldn't work because my body was telling me, 'You can't work.' So it wasn't that, but it was the fact that having it acknowledged and confirmed, literally I went suicidal to be honest with you. I got some help and I've been working on it ever since but, yes, I'm still battling with it. But, yes, it had a major impact on me.

No decision-making transparency, no objective records

Most claimants did not expect an accurate guide to the way WCA decisions are determined. But it appears that none of the way these decisions are made was shared with claimants at any stage. This meant people were not always able to make sense of their assessment decisions. They also could not understand exactly how their capabilities were judged. This was especially crucial if they wanted to appeal.

Currently, no objective records of assessments are made routinely available. The DWP’s current policy for recording of assessments states claimants have no legal right to a recorded assessment. The DWP has no obligation to provide them with one.

Audio recordings can be made available when asked for in advance, but this option does not seem to be advertised broadly. Access to assessment records is normally limited to the form filled at the assessment by the assessor. This is not offered to claimants but needs to be requested. One participant told us they managed to receive a copy of this form, but struggled to understand it as much of it was redacted:

I also requested a copy of my form, assessment, for my records after the appointment. I was sent around the houses obtaining it. Also, when it came it had more redactions than readable wording.

It is concerning that objective records are not available. There have been complaints on assessors' report. Several participants and survey respondents mentioned that assessors made false claims. Other times, they misrepresented what people had said on assessment records:

And they then actively lied on the form even though I was recording it.

Assessments are generally outsourced to third-party contractors. They are profiting from conducting these assessments:

…the attitude, the inaccuracies, the literally being brought to tears by DWP staff, by Capita, Maximus, you name it, new name third-party company employed by DWP.

Without an objective recording, most disabled claimants do not have evidence when trying to challenge accuracy of assessments and decisions or when complaining about assessors.

Experiences once awarded

Jobcentre engagement

Mutual suspicion

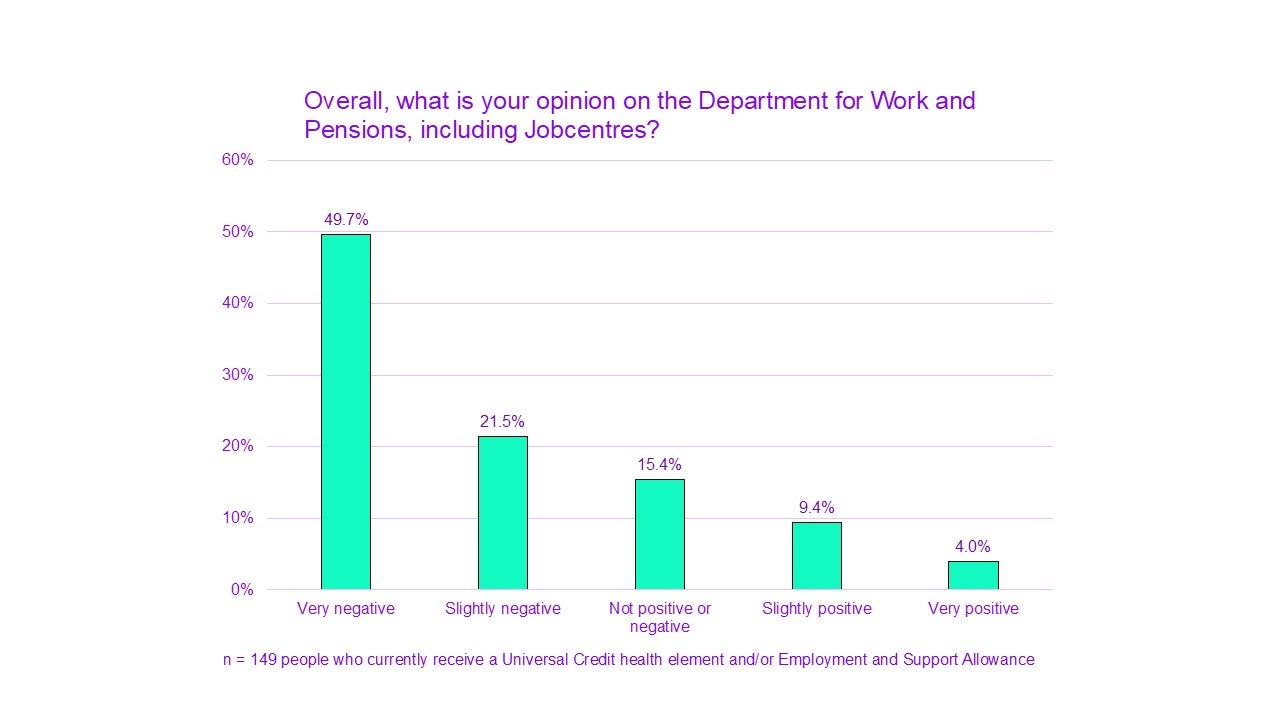

Claimants’ overall views of the DWP and Jobcentres were considerably more negative than positive. This is perhaps not surprising given the general lack of trust people have felt for the DWP over the years (Glover, 2019; Social Security Advisory Committee, 2020).

People have repeatedly mentioned feeling like they had to navigate the system’s suspicion towards them. People said that instead of being supported and understood, they felt monitored and penalised:

I think they put it on this sense of, 'We're watching what you do'. And it's that sense of they're waiting to catch you out when it's not necessarily that you're doing that, you're trying to just live your life. Everybody deserves to work, everybody deserves a sense of independence and do what they do, but it sometimes feels like you're punished for doing that in the way of if you want to go work, if you want to do something to get your independence back, they'll take that as a completely different sense of things in a way to gain more money back for the government than helping you.

Lack of communication and few to no contact options

Many claimants said they had very infrequent or no contact from the DWP, Jobcentre or work coach since they started receiving work-related disability benefits. This was nearly half for those receiving Limited Capability for Work and Work-Related Activity (LCWRA). This was part of what made Jobcentre employment support difficult to access for those who wanted or needed it.

![A chart titled "Since you started receiving [LCW, LCWRA or ESA], how often has [Universal Credit (UC) or] the DWP contacted you? This contact could be through the DWP, Jobcentre, or your work coach”.

I don’t know had 4.9% for LCW, 12.2% for LCWRA.

Never had 22.0% for LCW, 30.1% for LCWRA.

Less than once every couple of years had 7.3% for LCW, 13.5% for LCWRA.

Once every couple of years had 4.9% for LCW, 9.6% for LCWRA.

Once every year had 4.9% for LCW, 8.3% for LCWRA.

Once every 6 months had 14.6% for LCW, 6.4% for LCWRA.

Once every 3 months had 22.0% for LCW, 8.3% for LCWRA.

Once a month had 7.3% for LCW, 8.3% for LCWRA.

More than once a month had 12.2%for LCW, 3.2% for LCWRA.

n = 197 people. 118 currently receive a health element of Universal Credit, of which 31 have LCW and 87 and LCWRA. 79 currently receive Employment and Support Allowance, of which 10 are in WRAG and 69 in SG.](https://assets-eu-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/73ea709e-f9f8-0168-3842-ebd7ad1e23ac/4e2775fa-45e4-4c1a-8285-630fcfaa0870/Updated%20contact.jpg)

This was also true for when claimants had questions or needed benefit-related support. In our interviews and discussions, many have told us they struggled to contact the DWP or Jobcentre when they needed to:

… I also was just left without a work coach or anyone to be able to contact after getting put on LCWRA without warning.

A central communication tool is the journal. It is accessed through someone’s online Universal Credit account. This is used to update information, log required activities, and communicate about your claim. Claimants can leave messages for a work coach and receive messages back.

Many have told us they were directed to their journals with questions. Yet they received unreasonably late replies, and sometimes no replies at all:

If you've put a request into the journal you don't always get a reply. And you can write things several times and still not get a reply, and I think that's just rudeness. I know people are busy but it's their job to answer things on your journal. You've got no other way of contacting them, because if you ring up they say, 'Write it in your journal.'

A substantial amount of disabled people need support around their benefits. But there seems to be no service in place to support their needs as they come up and provide them with information. This means people were sometimes waiting for weeks, months or even longer for replies to their questions:

I've been asking for over a year and not been given an answer, even by employment work coaches, as they don't know, what income does our [National Insurance] NI contribution stop?

In some cases, this extreme lack of response left people in a helpless position and raised worries about sanctions:

I filled these journals in and they've not been looked at for weeks, I've asked a question and nobody's looked at it for weeks and weeks and weeks and then all of a sudden you get a response. But that's weeks down the line, you know, it's really difficult to even ring up your own local Jobcentre because it all goes through to one place to ask them a question. But you might need to contact that particular place to say, 'I can't come in and do this today.' And then you've not turned up and nobody's read your journal, nobody knows and then the next thing there's sanctions being applied.

This is also a significant barrier for those who are ready to move towards work. The difficulties with contacting the DWP or Jobcentre make it difficult to get support:

… I think the lack of communication in everything makes it so difficult overall to get anywhere with support.

Unsupported and misguided: difficulty accessing reliable information

Alongside the issues with communication, people struggled with the content of the answers they were looking for. It seems people were often not given clear, basic information about their benefits when they started to claim. So, they had to try and find information themselves. For many, it was difficult to receive accurate and reliable information about their rights and conditions. Even if they were current claimants at the Jobcentre:

I didn't know where to find the payments or anything like that, so I didn't know how to apply for an interim payment or anything because they don't tell you. You have to work it out yourself.” “You ask on the UC Journal and they give vague answers or incorrect answers.

It seemed that many struggled to find accessible information. One participant described their worries after being refused help from the DWP:

…Universal Credit is not clear, not transparent. And we are both autistic and we have both been asking for some organisation to provide us support, even the DWP and they've said, 'We are not an advice charity, we cannot provide support. Go to a charity.' There's no one that can provide us with that support. So, it literally feels like you could-, no, walking on eggshells. You could do anything, it feels arbitrary. You could look at somebody wrong in the Jobcentre and they could accuse you of abuse and you get your benefits sanctioned. Who knows what could happen?

Some described being misdirected, while others said they had to fight for things they knew they were eligible for. This was sometimes at a cost to people’s employment, financial or health situation. One participant, for example, was told they could not have a carer present at their job interview when they needed help to sign an expected contract:

Well, the only way or support I could do it is my auntie being there but I can't say this, 'Can my auntie come to an interview with me?' 'No.' How can she come in an interview and read anything to me? I have to read it by law. If I can't read it, how can I sign it? See where I'm stuck? I am stuck. I said this to the Jobcentre. They said, 'No, you can't take your carer to a job interview.' Thank you. 'That will look bad on you'.

Benefit details and permissions unclear

Following from the previously described issues, we found that a significant proportion of people were unaware or unsure about the details of their benefits. More specifically, people appear to be unsure about:

- Accurate award amount

- Work allowance: more specifically, LCWRA people were unsure about whether or not they’re allowed to work. They were also unsure how that might affect their award payments and entitlement

- If they were allowed to study while claiming

People explained they could see how much they were meant to be paid. Payment amounts are listed by element and by any other people on the claim. Deductions are also listed. But people often found these hard to understand. This means people were unable to work out if they were receiving the right amount. This made detecting underpayments very difficult.

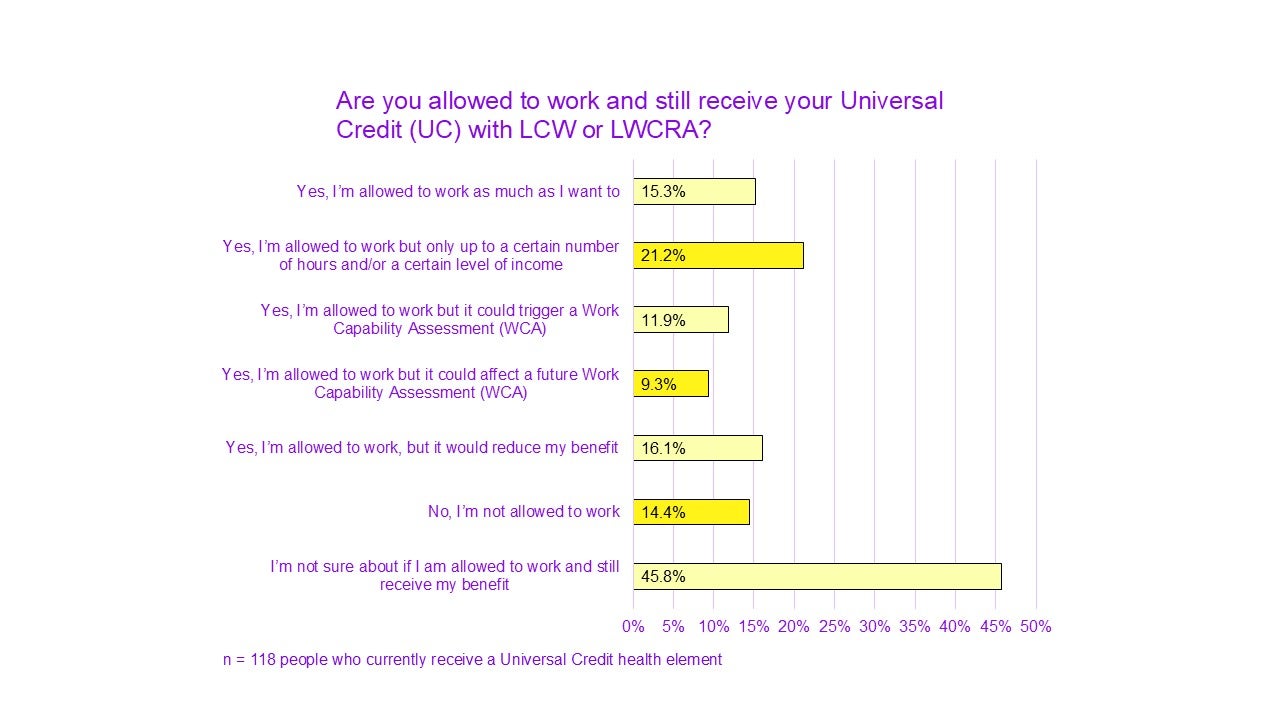

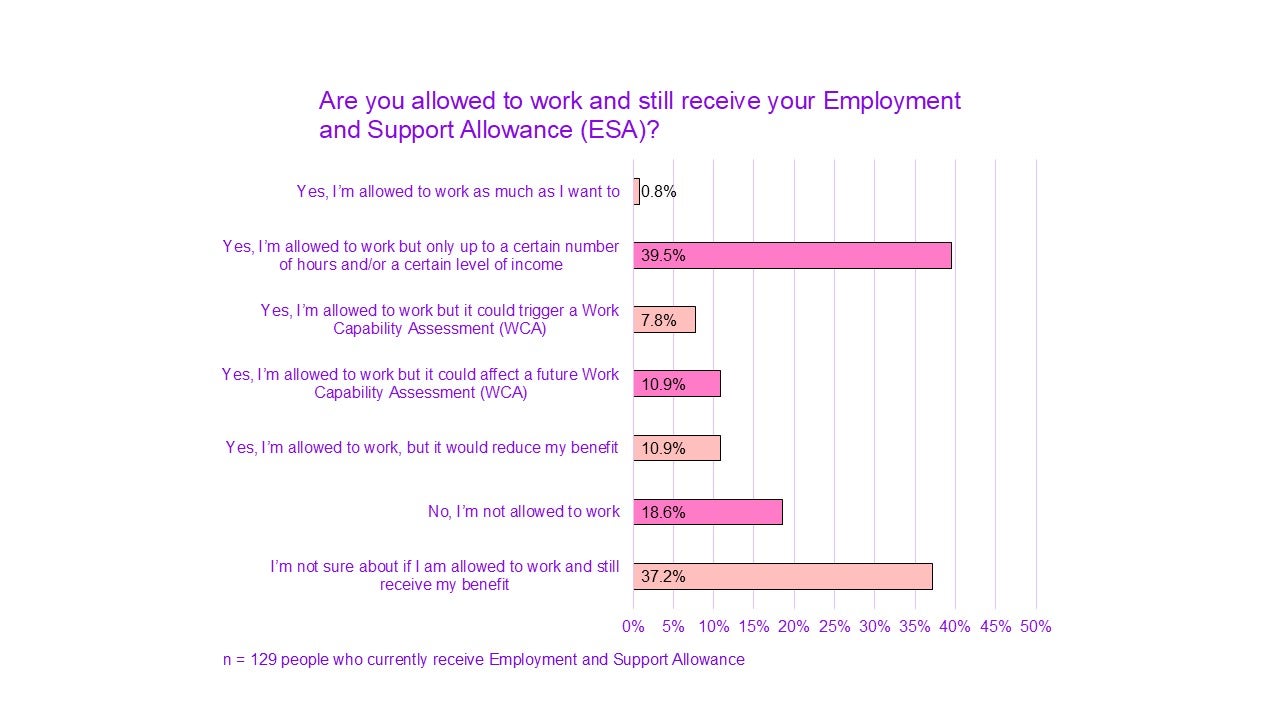

Disabled people receiving these benefits are allowed to work. But there are slightly different rules between each group.

Overall, we found that 41.3% of 247 UC and ESA claimants were unsure if they are allowed to work while receiving their benefit. Nearly 17% (16.6%) thought they were not allowed to work at all.

There was also belief that working could trigger a Work Capability Assessment or affect a future assessment. Even though these benefits are for people who have limited capability for work rather than no capability at all.

Some of the people we spoke to were working. This was particularly on a self-employed basis where they could control and limit the work they were doing when needed. But others who were interested in such options had been told they were more limited or were given inaccurate information:

I spent over a year arguing with the Jobcentre and Universal Credit about getting the correct information regarding me working. So, the whole time they gave me wrong information in regards to-, they kept saying you had a certain amount of work hours that you could do in a month, which isn't correct on limited capability work related activity. It's a work allowance which, again, they wouldn't give me, and then they did, they gave it to me wrong. I worked that out. And then when I went self employed they gave me so much wrong information and I spent 3 or 4 months trying to get an appointment to talk about it with a self employed work coach.

One participant had been told they could not do any paid work at all. They became quite distressed during a group discussion where other participants were discussing their work while receiving Limited Capability for Work (LCW) or Limited Capability for Work-Related Capability (LCWRA):

They did categorically tell me, 'No, you cannot do any work whatsoever. Anything you make, pound for pound, we take it out of your allowance.' That is news to me. I'd really like to be pointed in a direction of any information about that because to be perfectly honest, this is actually almost bringing me to tears because I just feel lied to.

People also shared they were not told about how the transition away from benefits would work, if their paid work took them over the work allowance:

I also read that your claim remains open for 6 months after you start working above your UC cut-off. I was never told this by anyone in DWP.

Work coach experiences

Compliance over support

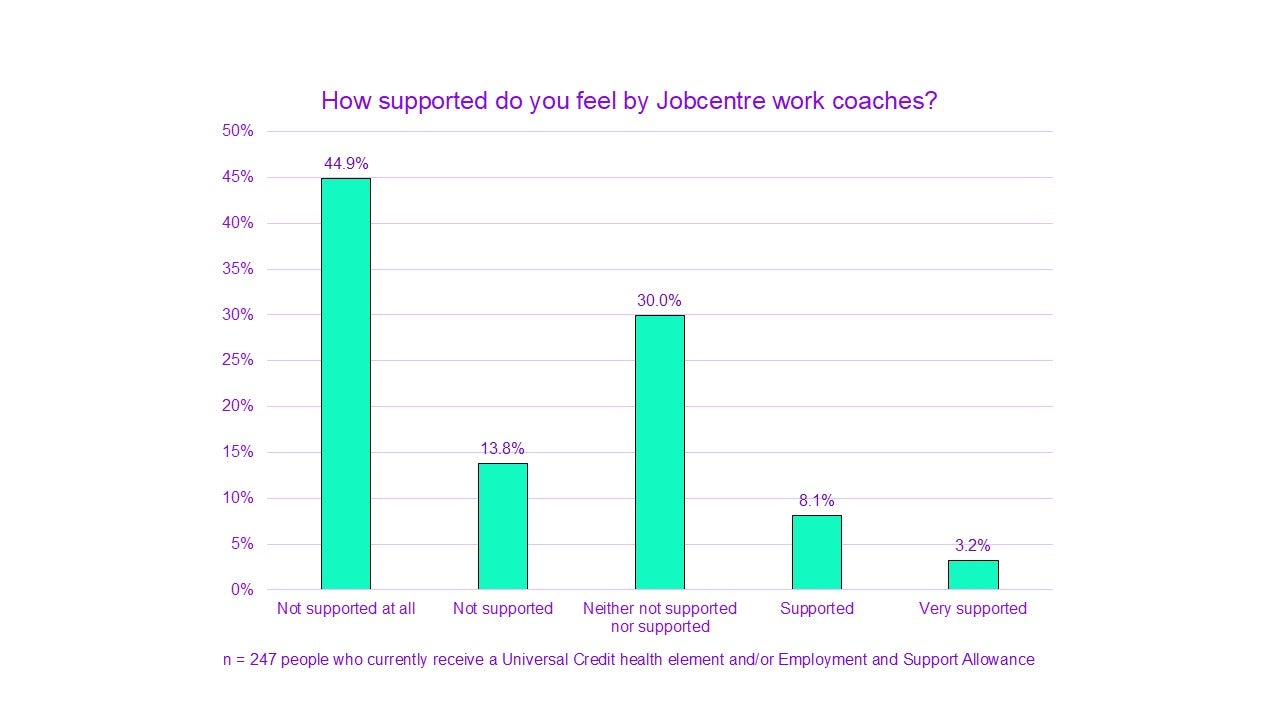

In line with people’s ratings of general views on DWP and Jobcentre support, we found only 11.3% of current claimants felt supported by work coaches.

This is likely linked to the low frequency and quality of contact people had with work coaches.

People generally felt looked down upon and inspected, and wished for a more supportive attitude:

The Jobcentre staff treat you like you're incapable and offer no actual helpful support. We have enough struggles with health conditions, so it would have been nice to feel like the coach has empathy, and a want to help.” “I think, the government sees it just as, 'We're paying you money. Prove to us that you need the money'. And that's it. There's no, sort of, actual support or comfort for us trying to live.

An unempathetic, black and white approach: no individual support

An experience that was very common among people interacting with work coaches was feeling a lack of empathy. People did not feel like their individual circumstances were heard and considered. They did not feel like work coaches cared much about their goals or needs. Instead, they felt decisions were made for them based on external considerations and targets.

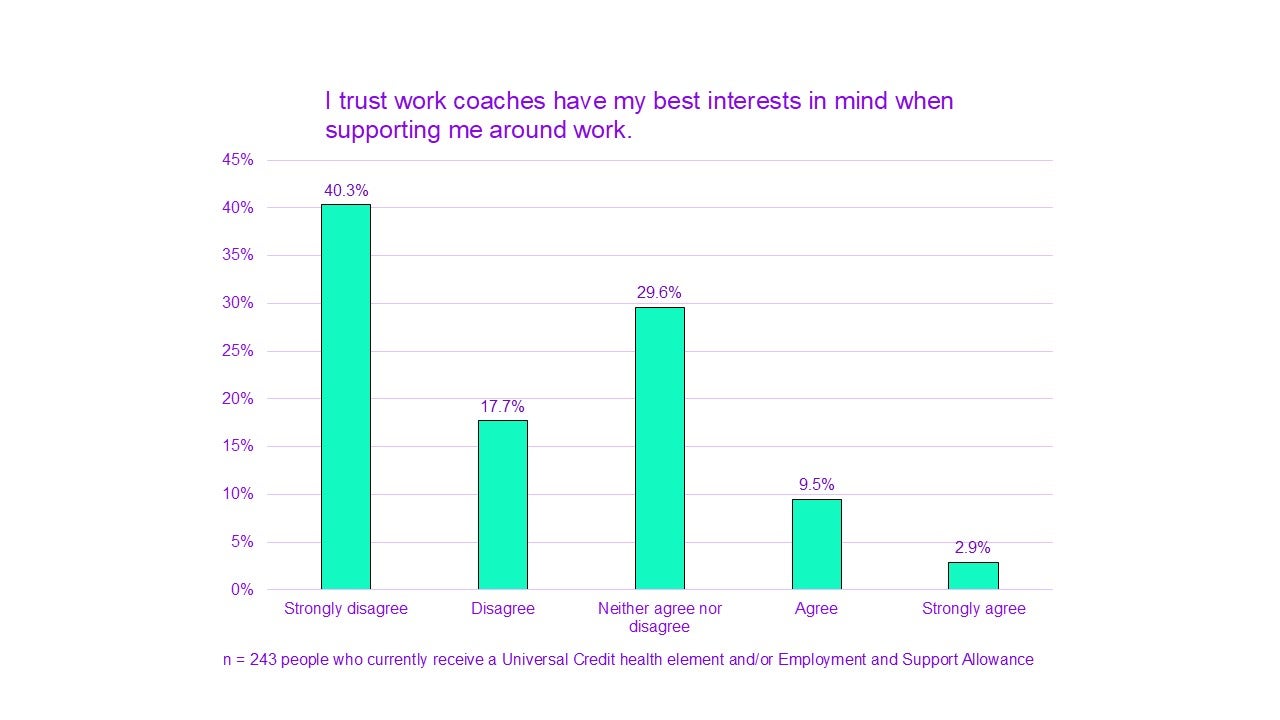

Only 12% said they trust work coaches to have their best interest in mind.

The binary approach that seemed to guide such decisions focused on labelling people as working or non-working only. This led to ignoring people's needs:

It's very much, sort of, they put everybody in 1 box and if you don't fit in that 1 box then, you know, you're not going to really get supported in the way you need.

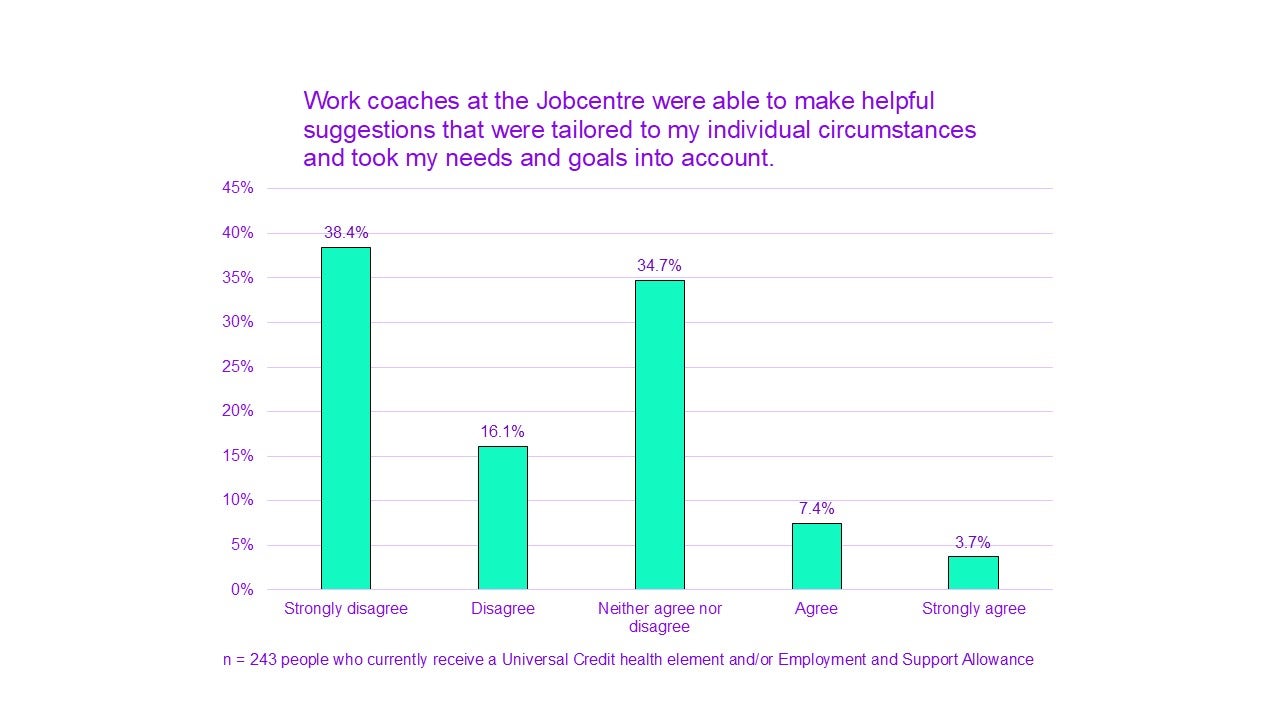

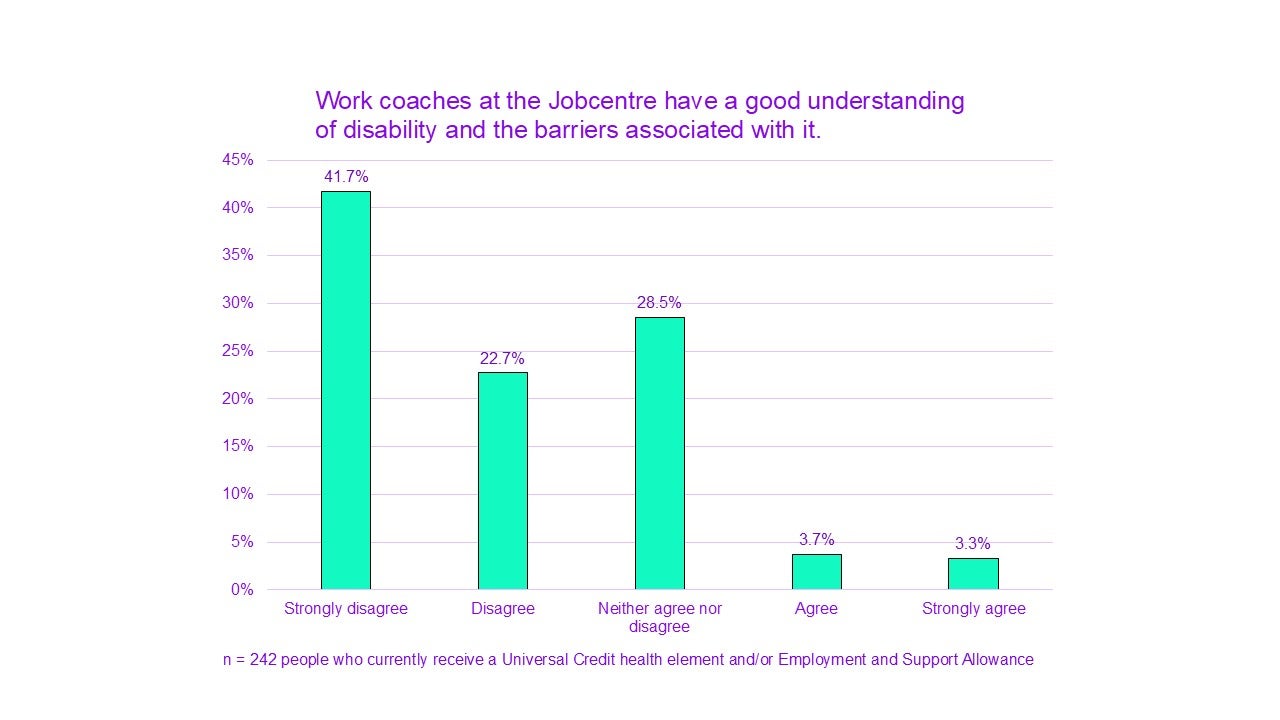

Only 11% said work coaches were able to make helpful suggestions based on their individual circumstances and needs.

There did not seem to be much room for efforts to find solutions to suit personal requirements. More specifically, people we spoke with said the type of things they felt were not taken into consideration were:

- individual access needs

- personal interests and skills

- the fluctuating nature of certain conditions

- flexible (few hours a week) and self-employment options

Some have said these types of harsh and uncompassionate interactions had a negative impact on their self-esteem and mental health:

..I feel like I was treated like, 'Oh, yes. It doesn't matter about that because we just want you to, kind of, find a job.' And even though they hadn't had a decision back yet that I couldn't actually work and that's the reason I had been let go from my last job at that time they didn't really, like, consider that. So, I think I went through probably about 3 or 4 different work coaches and they were all pretty much the same. So, it was, kind of, a really frustrating process when you're struggling with your health. And then, it also made my mental health decline. So, I was just, like, 'All I want you to do is just help me here, rather than, you know, just ignore me and make me feel like I'm not a human.

The obligation attached to those meetings with work coaches has made such experiences feel even worse: